You’ve chosen the perfect cell line for you, so the hard part is over. But how do you go about getting it? Do you ask a collaborator? Shop online? Make it yourself? In this guide, I’ll talk you through the pros and cons of each of these options so that shopping for cell lines doesn’t become a headache

Repositories and Commercial Suppliers

These are often an excellent place to start, and there are many different options! The American Type Culture Collection (ATCC®) [1], the Coriell Institute for Medical Research (NIGMS) [2] and the European Collection of Authenticated Cell Cultures (ECACC) [3] are large, well-established repositories that supply cell lines to labs all over the world. Many countries have repositories so you can shop more locally – check out the World Federation for Culture Collections (WFCC) [4] website to search. You can also buy cell lines from well-known life science brands such as Sigma or Thermo Fisher. [5] These companies typically have smaller collections, but they are usually partnered with big repositories as well.

Pros

You can avoid many potential issues by buying from an established cell line repository or commercial supplier. Any cell line you buy from one of these sources should be authenticated, contamination-free, and at a low passage number. Authentication of cell lines is one of the most critical issues in cell culture, so having a certificate of authentication ensures you can sleep at night knowing your paper won’t be retracted.

These sources also have:

- High standards of quality control.

- Expert knowledge and advice on the different cell lines they have available.

- Procedures to ensure cell lines will be appropriately handled and shipped so that you get high post-thaw recovery rates and aren’t wasting your money.

Repositories like the ATCC or ECACC have thousands of different cell lines representing many different species, genetic conditions, and diseases. Some suppliers specialize in mammalian cell lines, or specific human genetic conditions or diseases, and some have ‘exotic’ cell lines, so you know you’ll most likely be able to find the cell line you want.

Cons

The main disadvantage of buying cell lines from reputable suppliers is the cost, but it’s essential to have the correct frame of reference here. Purchasing a cell line from a repository will be more expensive than just getting it from your collaborator in another lab, but it will potentially save you more money in the long run. This cost-saving is because you won’t have to go through the hassle of authenticating it yourself, testing for infections, or any more significant issues down the track.

Although it may seem these repositories possess every cell line imaginable, this is not always the case – they generally only have those that are of interest to multiple researchers. If you’re after a cell line this is incredibly rare or not frequently used, you might have a more difficult time finding it at a repository. If this is the case, you might need to try the options below.

Collaborators

Partnerships are what makes science work, and not enough can be said about having reliable collaborators. If you’re looking for a rare cell line that you can’t find at a repository, collaborators may be able to provide it for you. Collaborators can be someone from your institution, a friend at another lab across the country, or someone you met at a conference. Don’t be afraid to send an email to the author of a paper you read that used the cell line you need – chances are they’d be happy to send you a tube of cells, and it opens the door for future collaborations!

Pros

A tube of cells that you get from a friend or another lab will be much cheaper than from an established source, which can be a big issue if you have a tight budget. If it’s someone from your university, you’d also save on shipping costs, which is another advantage.

If you need a cell line that isn’t ‘popular’ or is specifically gene-edited, then it might not be available from a commercial supplier, meaning a collaborator might be your best option. They may also be a more approachable source of technical assistance and advice on how to culture it, so you don’t have to worry about sending a bunch of emails to the customer service department.

Another major pro here is that if you’re using the same cell line as a collaborator, you can be reasonably sure you’ll get comparable results (and save yourself a troubleshooting session).

Cons

Based on the pro section above, you might be convinced that you should just call your postdoc friend in another lab and get them to send you their cell line. But can you be 100% sure that your friend gets all their cell lines authenticated, tested regularly for infections, and implements the gold standard for treatment of cell cultures in their lab? Probably not.

Unfortunately, even the most experienced and well-meaning person can make mistakes in the lab, and human error is one of the leading causes of contamination and problems in cell culture. You also can’t be sure the cells were frozen in a manner that will ensure they survive transport. If the cells are sent to you from another country or university, they’ll most likely need to be shipped on dry ice or liquid nitrogen, and this increases the cost. The cells also need to be at a low enough passage number for you to continue using them.

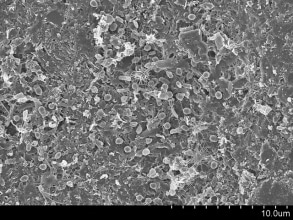

If you do get cell lines from a collaborator, make sure you authenticate them and test for infections immediately (and quarantine them while you do). And remember, not all infections are noticeable – you could have a mycoplasma infection in your cells and have no idea until it’s had significant impacts on your research. Mycoplasma shouldn’t be taken lightly, as they represent one of the primary sources of contamination in cell culture globally. You can send samples to a company for testing, buy a kit, or use a homemade PCR mycoplasma detection assay to do it yourself.

DIY Cell Lines

Unfortunately, sometimes you just can’t get the exact cell line you need from a company, repository or collaborator. Maybe you’re investigating a rare or novel genetic disorder, and the cell line simply doesn’t exist yet, or perhaps you’re studying a new species, and no-one has isolated cells from it before. If this is the case, you might just have to make it yourself. Making your own cell line can be challenging, but you’ll probably feel like an absolute cell culture wizard if it works.

Pros

Apart from feeling a smug satisfaction, the main benefit of creating a unique cell line is that you can engineer it to the exact requirements you need, instead of working with a standard cell line that’s just ‘close enough’. And while it may seem daunting, engineering a cell line doesn’t have to be complicated. [6]

You can find out how to immortalize your cell lines, and once you have, consider sending a sample to a biorepository for backup storage or for others to use.

Cons

DIY cell lines can be a challenge. If you’re going to genome-engineer a cell line, you’ll need the know-how, especially which methods are most likely to be successful for your target. For example, CRISPR isn’t efficient across the entire genome, so depending on where your target region is, it might not be the best option for you.

Making cell lines can potentially be a time-consuming, costly, and sometimes inefficient process – not ideal for those working on a tight budget or a strict schedule (and aren’t we all?). It’s probably a good idea to exhaust all the other possibilities rather than jumping straight to this option.

Hopefully, this article gave you a better idea of where to find reliable sources of cell lines. Tell us which option you chose and why in the comments below!

References

- American Type Culture Collection. Accessed 24 March 2020

- Coriell Institute for Medical Research. Accessed 24 March 2020

- European Collection of Authenticated Cell Cultures. Accessed 24 March 2020

- World Federation for Culture Collections. Accessed 24 March 2020

- Cell Lines. Thermo Fisher Scientific. Accessed 24 March 2020

- Jennifer Ellis. Cell-Line Engineering Doesn’t Have to Be Difficult. Future Labs. Published 8 February 2018.