It is the black death of cell culture. Scientists don’t dare utter its name and many a graduate student has fallen victim to its indiscriminate menace. These stealthy anarchists infiltrate quietly but deliberately until their numbers swell and then they attack in strength, overwhelming their victims before they can put up a fight!

What is mycoplasma?

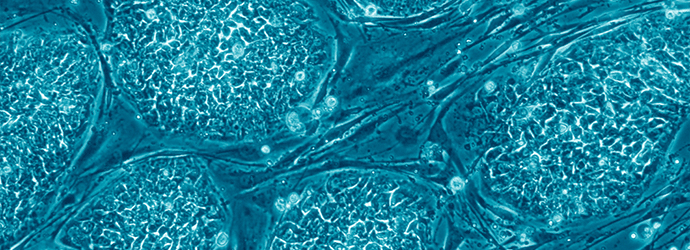

Who are these skilled agents? They are mycoplasmas, the smallest – around 100 nm in size – self-replicating living organisms and the simplest form of bacterium. However, unlike other bacteria, they lack a solid cell wall and instead have a plasma-like barrier. Mycoplasmas are parasites that invade a cell in large numbers, change the expression of hundreds of a host’s genes to hijack protein synthesis and biosynthetic machinery to fulfill their own energy needs.

As a result of their miniature size, these cellular saboteurs can go undetected in culture for very long periods of time because they are invisible to the naked eye and don’t cause culture turbidity or morphological cell changes. They are also resistant to a large number of commonly used antibiotics.

There are currently almost 190 different mycoplasma species but the majority of cell line contaminations can be traced to six species; M. orale and M. hyorhinis are the most common species that have historically accounted for more than 50% of all mycoplasma culture contamination (Drexler et al., 2002; Barile et al., 1973).

History of Mycoplasma

Mycoplasma were first isolated at the Pasteur institute in Paris in 1898 by Nocard and Roux as the causative agent of contagious bovine pleuropneumonia, which was a serious and widespread bovine disease at the time. In 1956, Robinson and colleagues reported the first contamination of cell culture by mycoplasma. By the 1960s, this discovery led researchers to believe that mycoplasma had become the major source of cell culture contamination, with mycoplasma cell culture testing conforming that between 60 to 90% of all cultured cells harbored mycoplasma.

Origins of Mycoplasma contamination

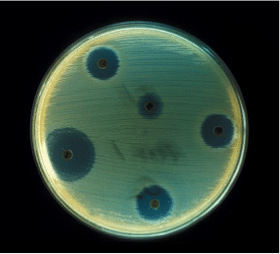

Mycoplasma contamination can be attributed to two main breakthroughs in cell culture in the 1940s and 1960s. The first was the increased use of antibiotics in cell cultures. With the development of penicillin and streptomycin in the 1940s, researchers started adding these two antibiotics to cell cultures, which allowed long-term cultivation without bacterial contamination. However, because mycoplasma lacked a typical cell wall it was not susceptible to these antibiotics, allowing it to grow undetected in cultures. In 1973, Barile and colleagues demonstrated that cultures grown in antibiotics had a 10-fold higher mycoplasma contamination rate than cultures grown without antibiotics.

The second contributing factor was a switch from human and horse sera to commercially prepared fetal bovine serum (FBS) as the traditional media supplement. Whereas human and horse sera was obtained from healthy volunteers and animals, FBS was prepared from blood obtained in the slaughter houses that was sterilized using 0.2 µm pore membrane filters to remove microbial contaminants. However, because mycoplasma was smaller than the filter pores, it could pass easily into the sera virtually undetected. This “mycoplasma-bearing” FBS led to mycoplasma contamination in many cell cultures without the scientists’ knowing. By the 1980’s, serum suppliers started using 0.1 µm pore membrane filters to eliminate mycoplasma from serum, but by then innumerable cell lines had already fallen victim to mycoplasma contamination.

Bitesize Bio has some excellent articles with tips to overcome mycoplasma and comparison of mycoplasma detection kits.