Not sure what we mean by cell passage number? Confused about how to calculate it and keep track of your culture’s passage number? Wondering if there is a maximum number of passages you should perform? We’ve got answers to all these and more.

What Do We Mean by Cell Passage?

Cultured cells, if provided adequate space, nutrients, and environmental conditions, will grow logarithmically. However, they reach a point where space becomes limiting, and if no intervention is taken, cell growth will slow, and cells will begin to die.

This is why you need to check the confluency of your cells regularly, and once they reach about 80% confluency, you need to ‘split’ or subculture the cells. This is also known as passaging your cells.

So What is a Cell Passage Number?

Cell passage number is simply a calculation of the number of times you have split or passaged your cells. Each time you go through that process, you should increase the passage number (p number) by 1.

Passage numbers are usually written on the flasks or plates of cells in incubators, and on cryovials when cells are frozen down. This provides a simple and easy way to keep track of passage numbers.

Why Do We Need to Monitor and Record Cell Passage Number?

Immortalized cell lines, including HeLa, HEK293, and U2OS cells, are often characterized by genetic instability, making them prone to changes over time.

In addition, culture conditions may offer selective pressures that result in a change to the population of cells over time (e.g., fast-growing cells will out-compete slower-growing cells).

Therefore the composition of cells at a lower cell passage number (e.g., p=3) may have very different properties and behavior to those of higher passage cells (e.g., p=40).

Primary cells tend to be much more genetically stable than immortalized cells. However, they often undergo senescence after a certain number of cell passages and can still be impacted by selection pressures.

Changes brought about through genetic instability, or selection pressures may result in phenotypic changes and affect how cells respond to treatments or experimental conditions. This could impact the accuracy and reproducibility of your results.

Recording the passage number allows you to keep track of the ‘age’ of the cells, and it is advisable to retire cells after a defined number of passages to keep your experiments reliable.

It is also recommended to keep a record of the passage number of cells when you perform any experiments, as this allows you to consider the passage number if there are any anomalies in your results.

What is the Maximum Passage Number for Cells?

What do we mean by high-passage cells? Determining the maximum passage number for cells is akin to asking how long is a piece of string. In terms of how long you can theoretically passage cells, that depends on the cell line. Immortalized cell lines can, in theory, be passaged indefinitely. However, as we discussed above, they may experience phenotypic and population changes due to genetic instability and selection pressures over time.

Practically speaking, cell passages should be limited to prevent population and genetic drift, and ideally, experiments performed with similar passage numbers.

There is no defined maximum number of passages you should perform for a cell line, but it is highly recommended to keep passage numbers low.

What is meant by low, however, can be varied, with some recommendations suggesting cell passage numbers be limited to no more than 10–20 passages, [1] while there are general guidelines in the healthcare and pharmaceutical settings that passages should be limited to a maximum of five. [2]

Common Questions About Assigning Passage Numbers

There are a few common questions that crop up when discussing cell passage numbers, which we’ve addressed below to allow you to stay in the know.

What Passage Number Should I Start At?

So you have a new culture, either from a frozen stock, from a supplier like ATCC, or from a fellow lab. Do you reset the clock and label your first passage 1? Or maybe you start at 0?

No matter where you source your cell stocks from, the cells you purchase have likely already undergone several passages. Suppliers should inform you of the passage number of the stocks you are purchasing, and you may find you need to pay a premium for stocks with passage numbers of 2 or less. If you are retrieving cell stocks from your lab’s frozen supply or have cells donated from another lab, you should ensure you ask for the passage number of the cells.

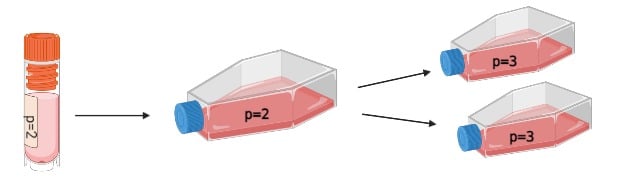

You should then continue the passage number from this supplied passage number (Figure 1). Note that the process of recovering cells into culture from the stock does not count as a passage.

If the stocks you are supplied with have a passage number of 2, the passage number you would write on the flask you initially grow them into would be 2. Only when you then subsequently subculture them would you increase the passage number to 3 (Figure 1).

Does Freezing and Thawing Cells Count as a Passage?

Figure 1 above explains how to set passage numbers from cell stocks. But what if you are freezing your cells yourself and then thawing, does the process of freezing and thawing cells count as a passage?

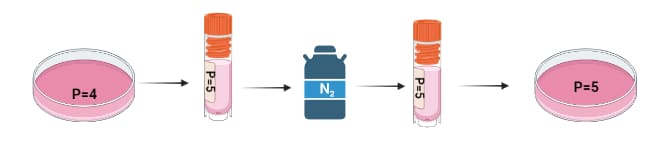

Let’s again look at a visual to help explain this. Say you have a stock plate of cells that you want to freeze down for later use that have a passage number of 4 (Figure 2).

For adherent cells, you would need to trypsinize (or detach the cells in some manner) from the plate before preparing the cells to be frozen. This step is a subculturing step, meaning that the passage number of the frozen stocks should be increased by 1 to 5. That means you would write on the vials that p=5 for these stocks.

You would not need to increase this number when you first recover the cells, only when you subsequently passage them (Figure 2).

How Can I Maintain Low Passage Numbers?

There are several practices you can do to ensure you are working with low passage number cells:

1. Buy your stocks from a reputable cell source, such as ATCC.

Buying stocks from questionable suppliers or getting them from other labs means you may not have reliable passage numbers, because of variations in freezing and subculturing protocols and how passage numbers are assigned.

2. Freeze stocks early on.

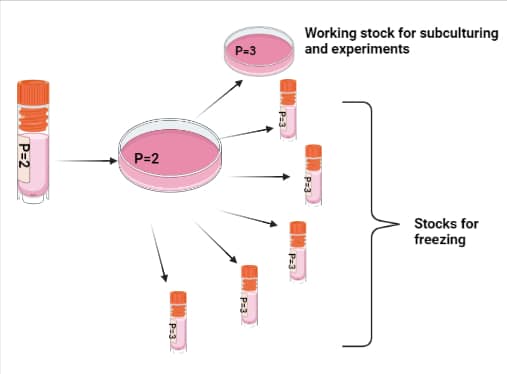

When you get and recover your stocks, you should passage them and then freeze stocks from this first round of passaging (Figure 3). This provides you with a set of low passage number stocks to return to when your working stocks reach the upper passage limit.

The Problem with Passage Numbers

After spending all the above time telling you about how passage numbers work and how to use them, it’s time to point out a big problem with passage numbers.

The purpose of recording passage numbers is to keep track of the ‘age’ of your cultures. However, passage numbers are not necessarily the best or most accurate way to do this.

Passage number is not accurate, because there can be big variability in how you and others passage your cells.

Say you split your 80% confluent cell culture at a 1:2 ratio during passaging. This means that your cells will undergo one doubling before being ready to passage again.

If, on the next round of passaging, you split your cells at a 1:4 ratio, then your cells will undergo two doublings before being ready to passage again. Meaning they have gone through twice as many doublings as the previous passage.

And if your lab mate splits their cells at a higher ratio of 1:6 or even 1:10, those cells will have undergone even more doublings while still being technically the same passage number as your cells.

The more cell division (or doublings) your cells undergo and the longer they spend in culture (which is the case if they are split at a higher ratio) then, the more opportunity there is for genetic, phenotypic, and cell population changes and drift. You may even notice changes in cell morphology over time.

Doubling Number as an Alternative to Cell Passage Number

Given the problems outlined above, it may be preferable to keep note of cell doubling numbers alongside passage number, as this may provide a more reliable way to avoid genetic and phenotypic changes from impacting your experiments and results.

Read more about the benefits of tracking doubling numbers and how to calculate them.

References

1. The European Collection of Authenticated Cell Cultures (ECACC). Passage numbers explained. Accessed 28 October 2022.

2. ATCC. Reference Strains – How Many Passages are Too Many? Accessed 28 October 2022.

Originally published 1st May 2013. Reviewed and updated, October 2022.