For decades, the diffraction of light has placed a hard limit on optical microscopy. Conventional widefield and confocal microscopes can’t resolve features smaller than about 200 nm laterally, which means critical signaling compartments and the nanoscopic organization of synapse-associated molecules remain hidden.

The 21st century brought revolutionary super-resolution technologies, such as stimulated emission depletion (STED), structured illumination microscopy (SIM), photoactivated localization microscopy (PALM), and stochastic optical reconstruction microscopy (STORM). But these methods come with significant practical barriers. They require specialized, expensive hardware and complex software. Many suffer from slow acquisition times, making nanoscale imaging of tissue samples challenging e.g., visualizing fine neuronal circuitry or organelle substructure.

Expansion microscopy (ExM) solves this problem by using microscopes that many labs already own. Instead of addressing the resolution limit through chemistry.

Physical Expansion of the Specimen as a Resolution Strategy

In standard microscopy, you place a small sample under a microscope and use lenses and physics to magnify the light coming from it. In ExM, instead of optically magnifying the image, you physically magnify the specimen itself.

Enjoying this article? Get hard-won lab wisdom like this delivered to your inbox 3x a week.

Join over 65,000 fellow researchers saving time, reducing stress, and seeing their experiments succeed. Unsubscribe anytime.

Next issue goes out tomorrow; don’t miss it.

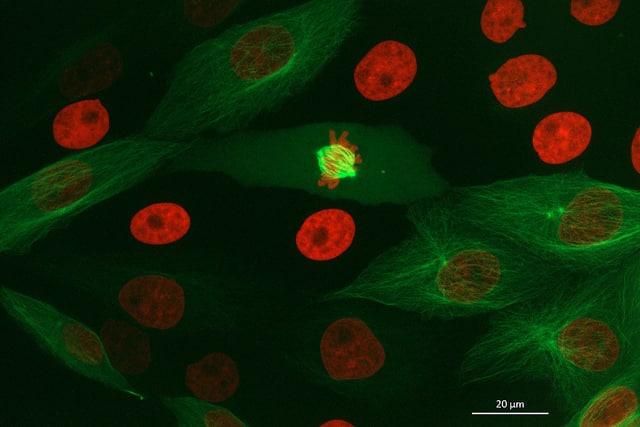

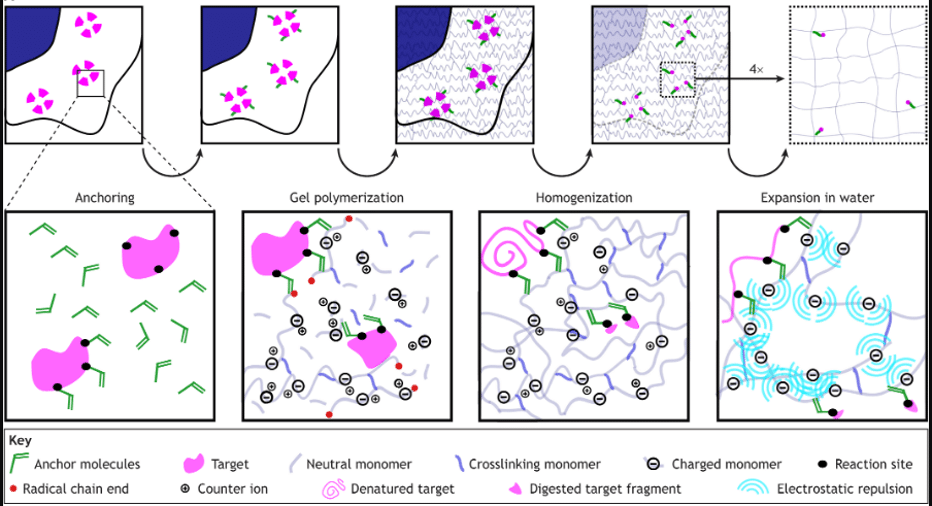

A swellable polymer network (a hydrogel) is synthesized throughout your specimen. By anchoring specific labels directly to this polymer network, the biomolecules in your sample can be physically pulled apart as the gel expands (Figure 1). This isotropic expansion results in a specimen that is larger in all directions. Structures that were previously closer than the diffraction limit become separated by distances your conventional lenses can resolve. Dense intracellular structures and signaling compartments become “decrowded,” allowing you to image them with standard equipment.

Because the sample itself has grown, features that required specialized super-resolution hardware now fall within range of conventional microscopes. This is why ExM is accessible to labs that could never justify purchasing a STED system.

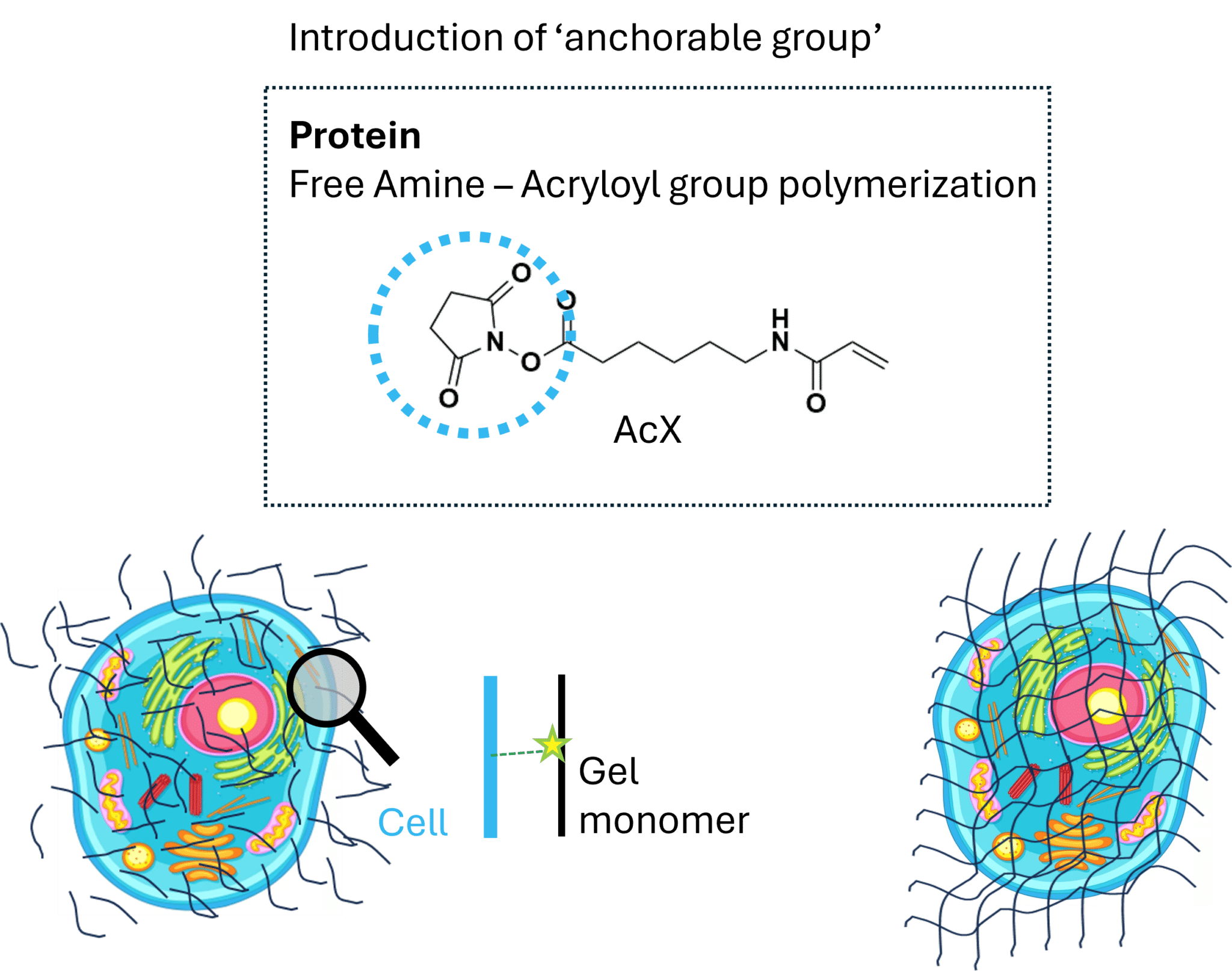

Figure 1: Anchoring biomolecules to a polymer network enables gel formation throughout the sample. Proteins within a fixed, labeled cell are first modified with an anchoring reagent such as AcX (acryloyl-X, SE). The NHS-ester group of AcX reacts with free amines on proteins, while the acrylamide group remains available for polymerization. When gel monomers are introduced and polymerization is initiated, these anchored biomolecules become covalently incorporated into a growing hydrogel network that permeates the entire specimen. This chemical linkage between biological structures and the polymer matrix is a critical prerequisite for subsequent expansion, ensuring that labeled features remain spatially registered to the gel as it forms.

Improving Effective Resolution by Physical Separation of Fluorophores

The effectiveness of ExM comes down to the relationship between the optical diffraction limit and the physical distance between fluorophores. If two molecules sit 50 nm apart, a standard light microscope will blur them into a single point.

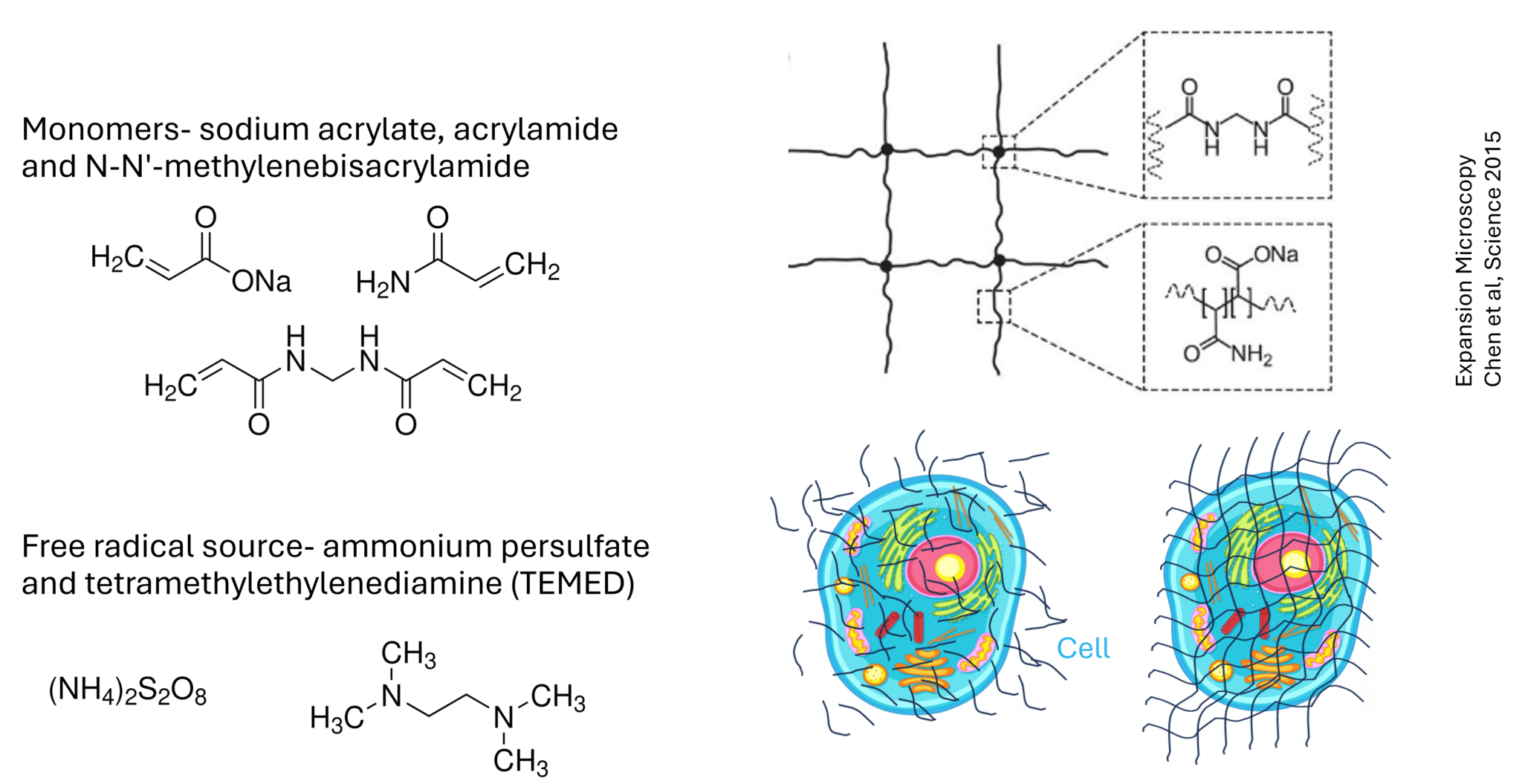

But by synthesising a dense, cross-linked hydrogel throughout your tissue (most ExM protocols use a poly(acrylate-co-acrylamide) formulation, Figure 2), you can expand the specimen linearly by approximately 4.5x in pure water. If your microscope’s lateral diffraction limit is around 250–270 nm, a 4.5x expansion yields an effective resolution of roughly 55–60 nm.

This process is designed to be isotropic, meaning the sample expands uniformly in all dimensions. This low-distortion expansion preserves the relative spatial organization of biological structures. While absolute distances change, the relationships between structures remain faithful to the original biology.

Figure 2: Chemistry and workflow underlying hydrogel formation in expansion microscopy. Schematic overview of the reagents and reactions used to form a swellable hydrogel throughout a biological sample. Monomers such as sodium acrylate and acrylamide, together with a crosslinker (e.g. N,N′-methylenebisacrylamide), are polymerized via free-radical initiation using ammonium persulfate (APS) and TEMED. Polymerization produces a crosslinked, charged poly(acrylate-co-acrylamide) network. When this network is synthesized throughout a fixed cell, anchored biomolecules become embedded within the gel matrix. Subsequent processing allows the gel–sample composite to swell uniformly, physically separating cellular components while preserving their relative spatial organization.

Equipment and Reagent Requirements for Expansion Microscopy

The primary advantage of ExM is accessibility. Unlike STED or STORM, which require distinct and costly instruments, ExM enables super-resolution imaging using reagents and hardware most biological laboratories already possess. The “super-resolution” aspect happens during sample preparation, not imaging. This shifts the barrier to entry from capital equipment to bench skills, a much more surmountable obstacle for most research groups.

Consider a lab with a standard confocal but no access to STED or STORM. Previously, resolving structures below 200 nm meant collaborating externally or accepting that certain questions were off-limits. With ExM, that same confocal becomes capable of around 60 nm effective resolution.

Because physical expansion brings nanoscale features into the range of diffraction-limited optics, you can use widely available widefield, epifluorescence, or confocal microscopes. And because the expanded tissue-gel composite consists of more than 98% water, it’s transparent, reducing scattering and aberrations deep into tissue. That said, imaging depth is still constrained by objective working distance and mounting considerations.

Chemical and Physical Changes to the Sample During Expansion Microscopy

Understanding these steps helps explain both the power and the limitations of ExM, and why optimization matters. The ExM workflow relies on four chemical steps to ensure biological information is retained while the physical structure enlarges (Figure 3):

Step 1: Anchoring Biomolecules.

You start with a fixed and fluorescently labeled sample. To ensure labels move with the expanding gel, they must be chemically anchored to the polymer network. A key reagent here is AcX (acryloyl-X, SE), a bifunctional linker. One end contains an NHS-ester group that covalently reacts with primary amines on proteins; the other end contains a free double bond that allows the biomolecule to participate in polymerization.

Step 2: Gelation.

Once proteins are anchored, you infuse the sample with a monomer solution, typically sodium acrylate, acrylamide, and cross-linkers. To initiate hydrogel formation, you add free radical generators such as ammonium persulfate (APS) and tetramethylethylenediamine (TEMED). These trigger a chain reaction that forms a polymer network throughout the sample. Because biomolecules are anchored via AcX, they become covalently incorporated into the hydrogel backbone.

Step 3: Homogenization.

Before expansion, you must break down the biological structure resisting it. Protease treatment, typically with Proteinase K, homogenizes mechanical properties by decoupling endogenous biomaterials from the expanding gel. This “softens” the sample while labels remain safely anchored, ensuring isotropic expansion without mechanical resistance.

Step 4: Expansion.

The final step is triggered by adding water. During gelation, high salt concentration shields charges on polymer chains. When you dialyze the sample in pure water, salt washes out, exposing highly charged carboxyl groups on sodium acrylate monomers. These negative charges repel one another, driving physical expansion. As the polymer network expands, it pulls anchored fluorophores apart, physically magnifying the sample.

Figure 2: Step-by-step schematic of the ExM workflow: 1. Anchoring, 2. Gel Polymerization, 3. Homogenization, 4. Expansion in Water. Taken from Nadja Hümpfer, Ria Thielhorn, Helge Ewers. Expanding boundaries – a cell biologist’s guide to expansion microscopy, J Cell Sci (2024) 137 (7): jcs260765.

Biological Applications Enabled by Expansion Microscopy

What biological questions does ExM make tractable that were previously impractical? ExM was initially developed for brain imaging, where it enables detailed mapping of densely packed neural connections. It has been used to resolve synaptic architecture, distinguishing between pre-synaptic and post-synaptic scaffolding proteins that appear as overlapping spots in conventional microscopy but separate clearly after expansion.

Beyond the brain, ExM helps resolve dense intracellular structures, revealing details previously accessible only through electron microscopy or high-end super-resolution systems. The technique is also compatible with large-volume imaging. By rendering tissues transparent and expanding them, ExM facilitates tracing long-range neuronal projections and identifying synapses across large tissue volumes. You can also combine ExM with other super-resolution techniques (like SIM) to push resolution limits further, potentially into the tens of nanometers.

Limitations and Trade-offs of Expansion Microscopy

While powerful, ExM isn’t a universal solution. A primary limitation is that it’s destructive. The chemical processing involves fixation, polymerization, and digestion, making it incompatible with live-cell imaging. You get a snapshot of a fixed state, not a dynamic view of biological processes.

Another significant trade-off is signal dilution. Because expansion is three-dimensional, a 4–5x linear expansion corresponds to 64–125x more volume. Fluorophores are distributed over this much larger space, reducing effective fluorescence intensity per unit volume, making dim samples challenging and increasing susceptibility to photobleaching.

Finally, the expanded hydrogel is physically fragile, mostly water, and lacking structural rigidity. Handle with care to avoid tearing. And if digestion isn’t thorough, samples may expand non-uniformly, leading to distorted images. A common misconception is that incomplete digestion simply reduces expansion factor; in reality, it creates local variations that introduce artifacts more problematic than low resolution.

Experimental Scenarios Where Expansion Microscopy Is Appropriate

Adopting ExM is often a decision balancing resolution needs against resource availability. If you’re already performing fluorescence microscopy but find spatial resolution limiting your data interpretation (distinguishing closely clustered proteins or tracing dense neurites, for example), ExM offers a practical path forward.

In practical terms, ExM is worth exploring if you need to resolve structures in the 50–200 nm range, you’re working with fixed samples, and you have access to a standard fluorescence microscope but not dedicated super-resolution systems. It’s probably not the right fit if your questions require live-cell dynamics, your samples are sparse enough to resolve conventionally, or you need resolution below 50 nm or so.

The transparency of expanded samples can reduce scattering for deeper tissue imaging, though working distance remains a practical constraint. The complexity moves from the microscope to the sample preparation bench. For labs willing to invest time optimizing anchoring and digestion chemistry, ExM provides a robust method to visualize the nanoscale world using tools already present in the room.

Further Reading

- Chen F, Tillberg PW, Boyden ES. (2015). Expansion microscopy. Science 347(6221):543–548.

- Gallagher BR, Zhao Y. (2021). Expansion microscopy: new dimensions in nanoscale imaging. Neurobiology of Disease 153:105280.

- Truckenbrodt S, Sommer C, Rizzoli SO, Danzl JG. (2018). A practical guide to optimization in X10 expansion microscopy. EMBO Reports 19(9):e45836.

You made it to the end—nice work! If you’re the kind of scientist who likes figuring things out without wasting half a day on trial and error, you’ll love our newsletter. Get 3 quick reads a week, packed with hard-won lab wisdom. Join FREE here.