Many proteins naturally form dimers, trimers, or larger assemblies but outside the cell, these states can be hard to track. They’re often unstable, sensitive to buffer or pH, or present at low concentrations.

Even subtle shifts in protein oligomerization [1] can significantly impact experimental outcomes. Variations in oligomeric states can alter a protein’s functionality, affecting enzymatic activity, binding affinity, and stability. These changes can influence the protein’s behavior in assays and its suitability for structural studies like crystallography or cryo-EM.

And while tools like size-exclusion chromatography (SEC), dynamic light scattering (DLS), native PAGE, or analytical ultracentrifugation (AUC) are useful, they often need more sample, more time, and sometimes still leave you guessing.

That’s where mass photometry [2] comes in. It’s a technique that lets you determine protein oligomerization without the hassle of the techniques mentioned above. MP allows higher sensitivity, and direct insights into mass, making it especially powerful for analyzing protein oligomerization, heterogeneity, or complex formation. This article explains how it works and shows you the type of data it generates.

Enjoying this article? Get hard-won lab wisdom like this delivered to your inbox 3x a week.

Join over 65,000 fellow researchers saving time, reducing stress, and seeing their experiments succeed. Unsubscribe anytime.

Next issue goes out tomorrow; don’t miss it.

What is Mass Photometry and How Does it Work?

Mass photometry (MP) is a quick, label-free technique that gives you a direct snapshot of what’s in your sample that is mass, heterogeneity, and relative abundance all from just a few microliters, and in minutes[3].

MP is a single-molecule technique that measures the mass of individual proteins or complexes in solution by detecting the light they scatter as they land on a glass surface. The amount of light scattered depends on how differently a molecule bends light compared to the solution, a property known as refractive index. The amount of scattered light correlates directly with molecular mass allowing you to identify different species in your sample and their abundance. Bigger molecules scatter more light, and by comparing the scattering signal to known protein standards, you can estimate the mass of unknown species with high accuracy [3].

For a basic MP experiment, you will:

- Place a small drop of ~10 ul of your protein sample on a clean coverslip

- As molecules land, a camera captures each light-scattering event

- The signal is matched to proteins with a standard mass (like BSA)

- A histogram is generated, showing how many molecules fall into each mass range

MP shows you each particle class in your sample: monomers, dimers, tetramers, and even aggregates.

Think of it like a group photo at a party: some stand-alone (monomers), some in pairs (dimers), others cluster (tetramers), and some form an indistinct crowd (aggregates).

What You Can Measure Using Mass Photometry

MP is fast, precise, and minimal in its demands. It works at near-physiological concentrations and requires no labels or modifications.

With just minimal amount of sample, you can:

- Directly measure protein mass and heterogeneity

- Detect rare species (as low as 1%)

- Monitor shifts in population under different buffer or pH conditions or mutations effects

- Evaluate sample quality before cryo-EM, crystallization, or binding studies

Several studies listed on Refeyn’s featured publications [4] page lists a wide range of peer-reviewed studies applying MP across biomolecular systems for various applications.

How Mass Photometry Compares to Similar Techniques

MP is a great first checkpoint before structural and functional studies. Think of it as a quality check. Since MP works at low nanomolar concentrations, it quickly shows whether your protein is monomeric, oligomeric, or aggregating. Proteins often behave differently at higher concentrations, but spotting heterogeneity early helps you decide whether to move ahead with SEC, cryo-EM, or go back and optimize the prep.

Each technique operates at different concentrations, which can influence the observed oligomeric state. DLS is one of the commonly used methods to analyze protein heterogeneity. While both MP and DLS provide size-related information, they measure different things. MP detects the actual molecular mass of individual particles based on how much light they scatter when they land on a coverslip. DLS, on the other hand, measures hydrodynamic radius by tracking how particles move in solution giving you an averaged size across the whole sample.

MP can distinguish similar species like dimers and trimers, even at low abundance, while DLS often misses them because larger particles dominate the signal. MP also works at nanomolar concentrations, closer to physiological conditions and ideal for limited samples. DLS usually needs higher concentration, which can lead to aggregation artifacts.

If you’re unsure which method to use for assessing oligomerization, Table 1 below summarizes the key features of the most commonly used techniques to help you decide.

Table 1. Comparison of common biophysical techniques used to assess protein size, oligomeric state, and sample quality.

Technique | Sample | Time | What you learn | When to use | Key points |

Mass Photometry | ~10 µL / 10 -50 nM | ~5 min | Oligomeric states, molecular mass, heterogeneity, | Early-stage checks, quick oligomer analysis, low sample availability | Fast, label-free, minimal sample, high-resolution, detects low-abundance species; ideal 40 kDa-5 MDa |

SEC + MALS | >200 µL (µM range) | 1-2 hrs | Mass, size (shape-dependent) | Confirming oligomeric state or size in stable, purified samples | Good for mass + size; limited for overlapping/mixed species, high sample amount |

DLS | ~50 µL (µM range) | Minutes | Hydrodynamic radius (average only) | Quick aggregation checks, rough size estimate | Fast, but low resolution; sensitive to aggregates, high sample amount |

Native PAGE | Variable | 2-4 hrs | Apparent size and charge | Basic screening | Inexpensive; limited interpretability in mixed samples |

AUC | >300 µL (µM range) | Hours | Mass, shape, stoichiometry | High-precision measurements for well-behaved, stable samples | Accurate but time and sample intensive |

What Equipment Do You Need?

Mass photometry needs a dedicated instrument—a mass photometer.

The system is compact and comes with built-in optics, a sample holder, and data analysis software. But even though the device is specialized, rest of the process is straightforward!

Here’s what you’ll typically need for a mass photometry experiment:

- Mass photometer: a small benchtop device with its own camera and detection system

- Glass coverslips: critical for signal clarity; usually ~$1-2 each if not cleaned in-house

- Silicon gaskets: reusable or inexpensive consumables to seal the sample area

- Calibrants or Calibration Standards: MP requires protein standards of known mass to convert scattering intensity into molecular weight. Refeyn offers a set of pre-calibrated proteins with defined masses (86, 172, 258, 344 kDa), covering the typical MP working range (~90 kDa to 1 MDa). However, labs often use their own standards given that the calibrants must be stable, well-characterized, and have defined oligomeric forms across the concentration range used.

- Software: Most mass photometry systems (like those from Refeyn) come with their own dedicated software (AcquireMP and DiscoverMP) designed specifically for acquiring data, detecting particle landing events, converting intensity to mass using calibration curves, fitting Gaussian peaks, and calculating species abundance. These built-in tools are user-friendly. There aren’t widely used free alternatives yet, but technically you can export raw data and analyze it using Python or ImageJ if you’re comfortable with custom scripting. Microsoft Excel can be used to create graphs based on the imported csv data values from DiscoverMP software. Therefore, most labs stick to the vendor software for reliability and ease, especially since it’s optimized for MP’s unique data format.

How to Determine Protein Oligomerization Using Mass Photometry

So now you know what MP is and the types of data it can give you, let’s get down to how to actually determine protein oligomerization using it.

MP gives you a real-time movie of individual molecules landing as black circles and a histogram that tells you exactly what’s in the drop. And you get all this information in about a minute!

MP processes your raw data by detecting landing events, converting contrast to molecular mass using known standards, fitting Gaussian curves, and calculating species abundance.

The resulting histogram typically shows:

- X-axis as molecular mass (kDa) and Y-axis as number of molecules detected

- Peak position = estimated molecular mass

- Height or area = relative abundance

- Sharp peaks = clean, well-defined species

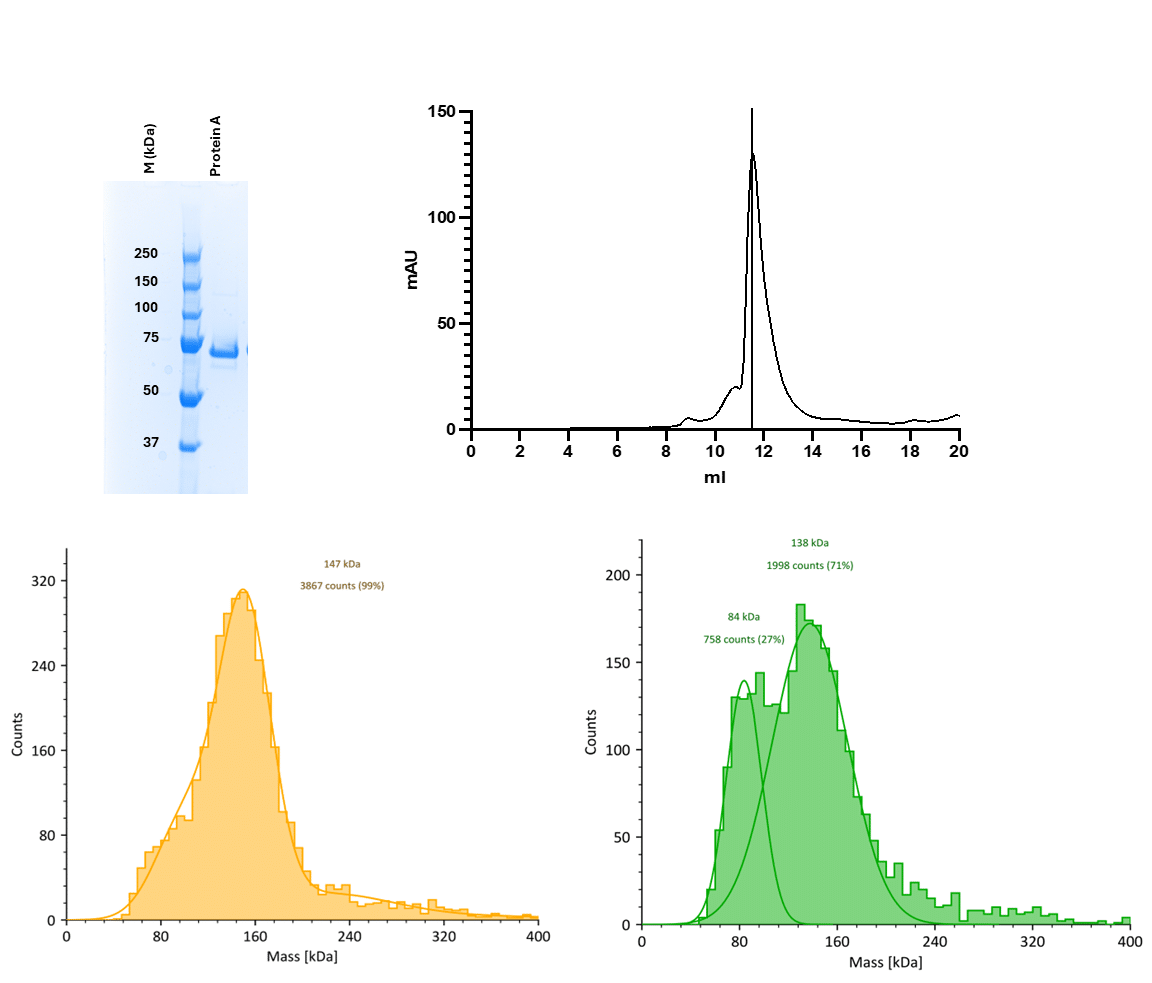

Note that broad or fuzzy peaks indicate the mixture if species or possible aggregation or instability (Figure 1)

Figure 1. (Top left) SDS-PAGE showing purity of the recombinant protein (1 µg), here arbitrarily called Protein A after size-exclusion. (Top right) Analytical size-exclusion chromatography (SEC) reveals a dominant dimer peak eluting around 11.5 mL, with no clear monomer peak detected. (Bottom) Mass photometry (MP) histograms of a dimeric peak fraction from SEC at two concentrations 40 nM (left) and 20 nM (right) resolve both dimeric and monomeric populations. Note that even at 40 nM concentration, the peaks are broad and indicate mixed populations. Gaussian curve fitting identifies a major species at ~147 kDa (consistent with dimer) and a secondary species at ~84 kDa (monomer), which becomes more prominent at lower concentration, suggesting dynamic equilibrium. This data provides a basis in one of our studies for calculating the monomer-dimer dissociation constant (Kd) using MP. It is interesting to note the low counts from ~240 to 400 kDa that might reflect higher oligomers and could be the result of aggregation (Unpublished data by Vandana).

Tips for Getting Reliable Results Using Mass Photometry

MP is user-friendly, but your prep matters. To get reliable results:

- Use ~10 µL of sample at 10-50 nM (20 nM is a good starting point)

- Aim for ≥90-95% purity (as assessed by SDS-PAGE or SEC)

- Spin and filter to remove aggregates or particles

- Use dust-free coverslips and clean silicon gaskets

- Calibrate using standard proteins with known molecular weights, oligomeric states, and stability

- Prepare clean, detergent-free buffers (Tris or HEPES, pH ~7.5); avoid high salt (>200 mM), glycerol (~2%), or reducing agents (≤1 mM)

Regarding the last point, you can optimize the precise composition for your protein sample if necessary.

Typical mass accuracy is within ±5%. That’s fine for most analyses, unless resolving closely spaced species (e.g., dimer vs. trimer).

Common Pitfalls in Mass Photometry and How to Fix Them

If your mass photometry results show fuzzy peaks, unexpected masses, or low particle counts, don’t worry, these issues are often fixable with a few key adjustments. Here’s how to troubleshoot common problems and improve data clarity:

- If your signal is weak, your protein concentration may be too low. Try increasing the concentration within the 10-50 nM range.

- If peaks are overlapping or poorly resolved, your protein concentration may be too high. Dilute the sample to reduce overlapping events.

- If your mass readings seem off, make sure to calibrate the system using well-characterized standard proteins (like BSA or thyroglobulin) before each session.

- If the image looks blurry or focus drifts, refocus the instrument before data collection begins.

- If your histogram shows odd scattering events, your coverslip may be contaminated. Always clean it thoroughly with isopropanol and water, and handle it with care to avoid dust or fingerprints.

- If particle counts are unexpectedly low, check if the sample was evenly mixed. Gently pipette up and down after dilution to ensure uniform distribution.

- If you see inconsistent counts, try equilibrating samples and buffers to room temperature before measurement to avoid temperature-induced artifacts. Temperature matters in MP because it impacts both protein behavior and optical conditions. Samples that are too cold or hot can change the buffer’s refractive index, promote aggregation, or alter protein folding leading to inaccurate scattering signals. Also, when running replicates, try to keep the time between sample dilution and measurement consistent across all runs.

- If the protein forms unexpected species, it may be degrading. Use a fresh prep to ensure sample integrity.

- If oligomerization patterns shift unpredictably, run a concentration series (e.g., 10, 25, 50, 100 nM). This helps detect concentration-dependent oligomerization, especially when studying mutant constructs or comparing conditions.

General tips:

- Document every small adjustment as minor changes can make a big difference and help refine future experiments.

- Use consistent buffer conditions and avoid additives like detergents or high salt unless tested and optimized for MP.

- Always clean the coverslip before each run using water and isopropanol, and dry thoroughly with an air duster.

When You Should Avoid Mass Photometry

Mass photometry is powerful, but like any technique, it has its limits and knowing them can save you time and plan better:

- Proteins <30 kDa may scatter too little light to be detectable (MP range is 30 kDa to 5 MDa proteins)

- Weakly bound complexes may dissociate at low MP concentrations and be missed in analysis

Complex mixtures without enough purity are tough to interpret. For reliable results, your protein sample should ideally be around 90-95% pure, as judged by SDS-PAGE or SEC. Remember it’s not just about purity, multiple species close in mass (e.g., partially cleaved protein, degradation products, or dynamic oligomers) can complicate the readout.

Mass Photometry Summarized. Make the Most of Your Time and Protein

Mass photometry provides fast, clear insights from minimal sample. It’s great for when you have a limited volume of protein or early decisions are needed, such as during construct screening, expression troubleshooting, or quality checks before structural studies.

While mass photometry (MP) is widely known for different applications [5] including resolving oligomeric states, conformational heterogeneity, and sample quality control for cryo-EM studies, you can use to characterize nucleic acid complexes [6], membrane protein assemblies [7], viruses [8] antigen-antibody [9], protein-DNA interactions [10], and protein-protein interactions [11]. MP is also useful in investigating how mutations [12] affect protein behavior and in estimating apparent dissociation constants of proteins [13].

References

[1] M. H. Ali and B. Imperiali, “Protein oligomerization: How and why,” Bioorg Med Chem, vol. 13, no. 17, pp. 5013–5020, Sep. 2005, doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2005.05.037.

[2] R. Asor and P. Kukura, “Characterising biomolecular interactions and dynamics with mass photometry,” Curr Opin Chem Biol, vol. 68, p. 102132, Jun. 2022, doi: 10.1016/j.cbpa.2022.102132.

[3] G. Young et al., “Quantitative mass imaging of single biological macromolecules,” Science (1979), vol. 360, no. 6387, pp. 423–427, Apr. 2018, doi: 10.1126/science.aar5839.

[4] Refeyn, “Featured Publications,” Refeyn Ltd. Accessed: Jun. 29, 2025. [Online]. Available: https://refeyn.com/featured-publications

[5] R. Asor, D. Loewenthal, R. van Wee, J. L. P. Benesch, and P. Kukura, “Mass Photometry,” Annu Rev Biophys, vol. 54, no. 1, pp. 379–399, May 2025, doi: 10.1146/annurev-biophys-061824-111652.

[6] Y. Li, W. B. Struwe, and P. Kukura, “Single molecule mass photometry of nucleic acids,” Nucleic Acids Res, vol. 48, no. 17, pp. e97–e97, Sep. 2020, doi: 10.1093/nar/gkaa632.

[7] A. Olerinyova et al., “Mass Photometry of Membrane Proteins,” Chem, vol. 7, no. 1, pp. 224–236, Jan. 2021, doi: 10.1016/j.chempr.2020.11.011.

[8] E. H. T. M. Ebberink, A. Ruisinger, M. Nuebel, M. Thomann, and A. J. R. Heck, “Assessing production variability in empty and filled adeno-associated viruses by single molecule mass analyses,” Mol Ther Methods Clin Dev, vol. 27, pp. 491–501, Dec. 2022, doi: 10.1016/j.omtm.2022.11.003.

[9] D. Wu and G. Piszczek, “Rapid Determination of Antibody-Antigen Affinity by Mass Photometry,” Journal of Visualized Experiments, no. 168, Feb. 2021, doi: 10.3791/61784.

[10] S. Balakrishnan et al., “Structure of RADX and mechanism for regulation of RAD51 nucleofilaments,” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, vol. 121, no. 12, Mar. 2024, doi: 10.1073/pnas.2316491121.

[11] D. Wu and G. Piszczek, “Measuring the affinity of protein-protein interactions on a single-molecule level by mass photometry,” Anal Biochem, vol. 592, p. 113575, Mar. 2020, doi: 10.1016/j.ab.2020.113575.

[12] B. Dadonaite et al., “Spike deep mutational scanning helps predict success of SARS-CoV-2 clades,” Nature, vol. 631, no. 8021, pp. 617–626, Jul. 2024, doi: 10.1038/s41586-024-07636-1.

[13] Z. Kofinova, G. Karunanithy, A. S. Ferreira, and W. B. Struwe, “Measuring Protein‐Protein Interactions and Quantifying Their Dissociation Constants with Mass Photometry,” Curr Protoc, vol. 4, no. 1, Jan. 2024, doi: 10.1002/cpz1.962.

You made it to the end—nice work! If you’re the kind of scientist who likes figuring things out without wasting half a day on trial and error, you’ll love our newsletter. Get 3 quick reads a week, packed with hard-won lab wisdom. Join FREE here.