I once had the terrible experience of not being able to run an assay because I ran out of my stock of chemically transformation-competent Escherichia coli E. coli. From that day, I learned to make my own chemically competent cells in the lab.

I recommend that everyone makes their own stash of chemically competent cells for three simple reasons. First, every molecular biologist should learn how to do it. Second, it is very straightforward. Third, it will save you money and prevent emergency situations.

Today, I will tell you how to make a DIY stock of chemically competent E. coli, the workhorse in the molecular biology laboratory.

Things You’ll Need

- Fresh overnight culture of any E. coli strain grown in LB broth.

- Sterile centrifuge tubes (e.g., for Beckman JA-17 rotor). Falcon tubes also work great.

- A spectrometer for reading the optical density of E. coli.

- Sterile, ice-cold CaCl2 at 100 mM.

- Sterile, ice-cold CaCl2 at 100 mM with 15 % v/v glycerol.

- Sterile Eppendorf tubes.

What Are Chemically Competent Cells?

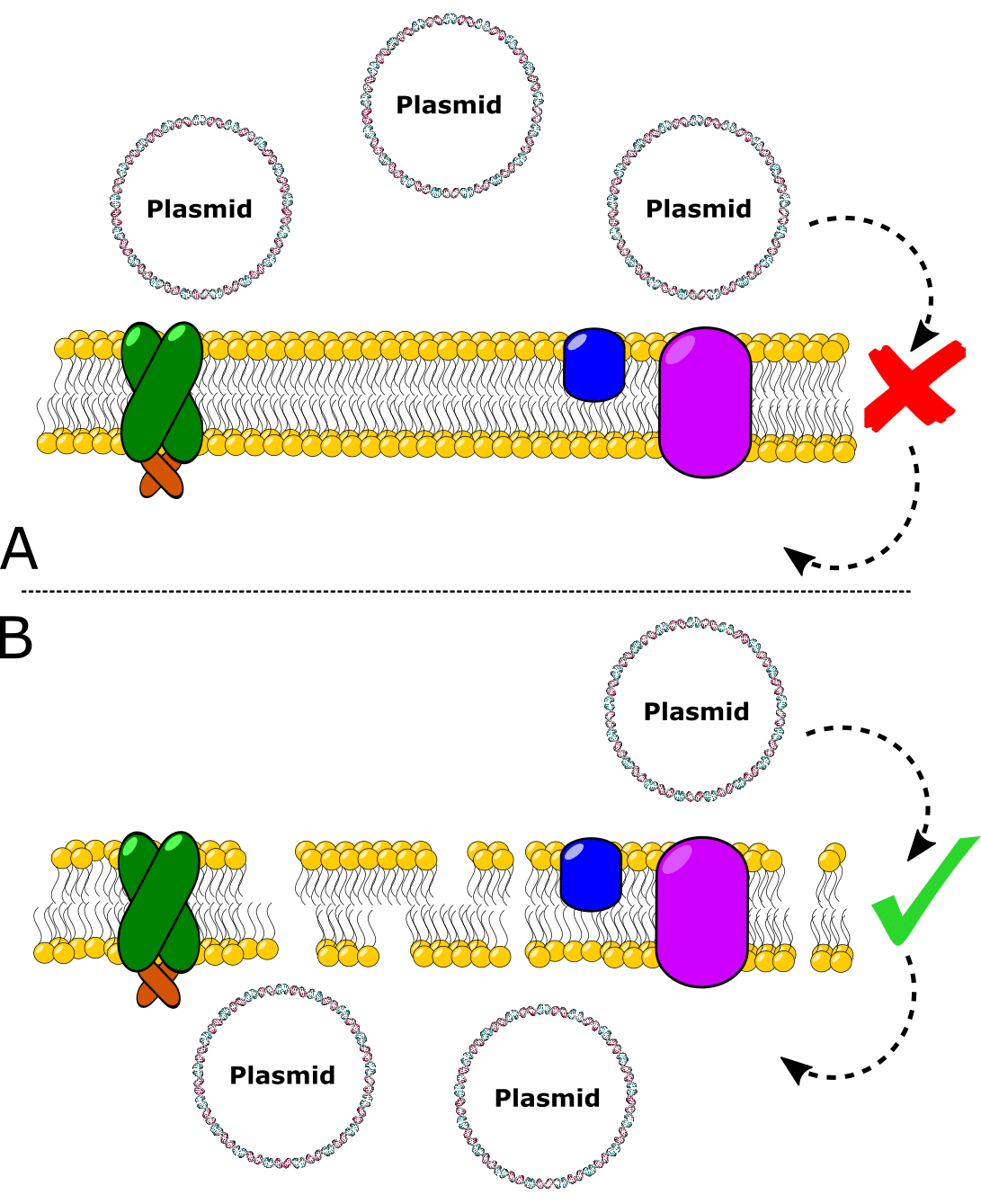

Chemically competent cells are basically bacteria that have been treated with chemicals to enable the bugs to take up exogenous plasmid DNA when the situation requires (your experiment).

The process of getting plasmids into bugs is called transformation, and chemically competent cells are transformed via heat shock.

And how do you make E. coli happy to take in foreign plasmids? You see, these little bugs do not normally just gobble up any foreign substances (plasmids included) for no reason. The trick is to disrupt (activate) the cell membrane of the E. coli so that the plasmid will be able to move across it into the cell.

The state of being able to take in exogenous DNA is called competency (Figure 1).

To prepare chemically competent cells, you need to grow a batch of E. coli from a small volume and subculture them. Then, collect the E. coli when they are actively dividing (during logarithmic growth). Because the population is in synchrony during logarithmic growth, the E. coli will be best prepared to become transformation competent.

So, collecting the cells during log-phase growth is crucial.

Also, when making a batch of chemically competent E. coli, we don’t add any antibiotics to the growth medium. This is because we are not amplifying any plasmids, which are what confer antibiotic resistance to the E. coli cells in the lab. So, take care with your sterile technique so as not to contaminate the cells during preparation.

After collection, treat the little bugs with a series of cold, salty buffer washes to render the membrane semi-permeable to plasmid DNA.

Aliquot the cells out, freeze them down at -80 °C, and hey presto! Your own batch of chemically competent cells.

A DIY Competent Cell Protocol

Here is a simple, step-by-step protocol to enable you to prepare your own chemically competent cells in the lab: [1]

- Go and prepare everything table 1 below and put it all in the fridge.

- Innoculate 10 mL of sterile LB with your desired E. coli strain. Culture overnight at 37 °C with shaking at 200 rpm.

- Reinnoculate 1 mL of the overnight culture into 99 mL of sterile LB and culture at 37 °C with shaking at 200 rpm until an Optical Density at 600 nm (OD600) of 0.3 – 0.5 (mid log phase) is reached.

- Split the 100 mL culture equally between sterile centrifuge tubes and collect the cells by centrifugation for 10 minutes at ~ 7000 rpm at 4 °C. Discard the supernatant and use a P200 pipette to remove any drops that remain.

- Add 20 mL of sterile, ice-cold 100 mM CaCl2 to each cell pellet and gently resuspend the cells. Allow the resuspended cells to chill on ice for ~ 15 minutes.

- Collect the washed cells by centrifugation for 10 minutes at ~ 7000 rpm at 4 °C and discard the supernatant.

- Add 5 mL of sterile, ice-cold 100 mM CaCl2 supplemented with 15 % v/v glycerol to each cell pellet and gently resuspend them.

- Divide the resuspended cells into 50 μL aliquots in sterile, ice-cold Eppendorf tubes.

- Store the chemically competent cells at -80 °C. They should remain competent for at least 1 year.

- Quantify the transformation efficiency of your chemically competent cells by transforming them with a known amount (say 1 µL of 10 – 50 ng/µL) of plasmid that contains a positive selection marker and count the number of transformant colonies.

Table 1. Solutions to prepare chemically competent cells.

| Components for → | 1 M CaCl2 | 100 mM CaCl2 | 100 mM CaCl2 with 15 % v/v glycerol |

|---|---|---|---|

| Anhydrous CaCl2 | 11.1 g | - | - |

| 1 M CaCl2 | - | 10 mL | 12 mL |

| Glycerol | - | - | 18 mL |

| Water | 100 mL | 90 mL | 90 mL |

Before You Get Started…

We all know that a clear protocol doesn’t always translate to an easy workflow and that insider wisdom goes a long way. Here are some useful pointers:

- It’s important to handle the cells gently because we’re weakening the cell membrane to make them chemically competent. This makes them susceptible to physical damage and a dead bug is a useless bug.

- Sterile, sterile, sterile. Remember there are no antibiotics in the culture, so it’s prone to contamination. Take particular care when checking the OD600 of the cells and aspirate the culture over a Bunsen burner.

- If you are making up competent cells for an entire lab group, and plan to fill (say) an entire box full of aliquots, then label all of the tubes whilst your subculture is growing. Then place these in a box in a -80 °C freezer to cool down.

- Also, grab a lab buddy and some liquid nitrogen in a wide-necked Dewar just before aliquoting the cells for storage. One of you can aliquot the cells into Eppendorf tubes and the other one can close the caps and place them in the liquid nitrogen to cool down. Remember, work quick and cold.

I really like the DIY movement in preparing lab reagents. Admittedly, we’re fortunate to be doing science in this era because there are so many “kits” available. However, it is always good to learn how to survive without them. These secret “personal stocks” can pay huge dividends when you’re in an emergency situation.

Plus, the DIY route is always budget-friendly and useful amid periods of financial austerity. So why not try your hand at making your own electrocompetent cells as well?

Have you found this protocol for preparing chemically competent cells useful? Have you got any additional comments or queries to add? Leave them in the comments section below if so. We’ve already reviewed and updated the article based on the comments below – so your comments are useful!

For a constant supply of high-quality competent cells, download Bitesize Bio’s chemically competent cells protocol cheat sheet—your reliable set of instructions to prepare chemically competent cells in the lab.

And for more tips, tricks, and hacks for getting your experiments done, check out the Bitesize Bio DIY in the Lab Hub.

Originally published August 2016. Reviewed and updated November 2021.

References

- Chang A et al. (2017) Preparation of calcium competent Escherichia coli and heat-shock transformation. JEMI Methods 1:22–25