Fixation is routinely used in histology and cytology labs the world over as a way of keeping cells in stasis at a particular point to ensure that, by the time they are examined, they have not deteriorated and the things you want to see are still there!

This is also something that we often want to do in flow cytometry experiments.

But there are several fixatives you can choose, and your sample type and downstream experiments impact your choice.

Read on for four fixatives for histology and cytometry. We’ll explain a little bit about each one and give you some top tips for perfect preservation. But first, let’s explain the importance of this process.

Why Should I Fix My Cells?

There are many reasons why fixing your cells is a good idea:

- It will allow you to run samples when you are ready (e.g., when a cytometer becomes available). This is particularly beneficial if you are doing a time-course assay or paying for cytometer access!

- You’ll be safer because your cells are no longer alive. In some labs, fixed samples may be mandatory.

- It is usually convenient and easy.

- If the antigen or target you want to look at is intracellular, you’ll most likely need to fix your cells in order to permeabilize them, allowing the antibody/dye to reach its target.

Fixatives for Histology

What are your choices if you want, or need, to fix your samples?

There are two commonly used classes of fixative:

- alcohols.

- aldehydes.

1. Alcohols

Alcohols, usually ethanol or methanol, are precipitating or denaturing fixatives that coagulate proteins. They will also dissolve lipids meaning that they will create large holes in the cellular membranes (plasma membrane and nuclear membrane).

Alcohols are generally good when you are interested in DNA analysis—coagulation of the proteins around DNA allows even access to the dye, leading to a good coefficient of variation (CV; low data spread).

But, as you may have thought, coagulation of proteins can be problematic if your antibody depends on a particular conformation of its target protein to recognize its epitope. So in very many cases, alcohol fixation will mean you will be unable to detect your protein even though it is there in the cell!

The exception to this will be small epitopes such as phosphorylation-specific antibodies.

2. Aldehydes

Aldehydes are cross-linking fixatives and create bonds chiefly between lysine residues. In this way, they keep the structure of most proteins intact, which makes them an ideal candidate for antibody staining as the epitope is more likely to remain intact.

3. Formaldehyde

So, technically 3 and 4 are examples of 2, but let’s skip over that technicality.

The usual aldehyde fixative used in cytometry is formaldehyde, which will polymerize to become paraformaldehyde (PFA) unless there is a small amount of methanol added to the solution. A common mistake is to say that paraformaldehyde is used to fix cells.

In reality, paraformaldehyde is an insoluble white powder that won’t fix anything—the solution we use is methanol-free formaldehyde.

For fixation purposes, it should be diluted with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) to a concentration of anywhere between 0.5% and 4%. For a more in-depth explanation of the nomenclature of formaldehyde and paraformaldehyde, see this message on the Purdue University cytometry web page.

4. Glutaraldehyde

Glutaraldehyde is extensively used in electron microscopy but is not as widespread in flow cytometry. This is because it is more effective at cross-linking than formaldehyde, making it harder for antibodies and dyes to stain structures effectively.

It also increases cellular autofluorescence markedly, so unless you have a particular reason for using glutaraldehyde, stick with formaldehyde or alcohol.

A Good Rule of Thumb

Bearing in mind what we’ve just discussed. Keep this in mind:

- Use formaldehyde for light microscopy.

- Use glutaraldehyde for electron microscopy.

How Long Will My Cells Last Once Fixed?

You’ll be pleased to hear that cells fixed in ethanol are stable at 4°C or -20°C for months.

For formaldehyde-fixed cells, this is reduced to around 1–2 weeks. Unlike ethanol-fixed cells, which can happily sit in ethanol all that time, you should spin cells out of the formaldehyde after 20–30 minutes of fixation, as prolonged storage in fixative will increase autofluorescence.

After this, they can be safely stored in PBS.

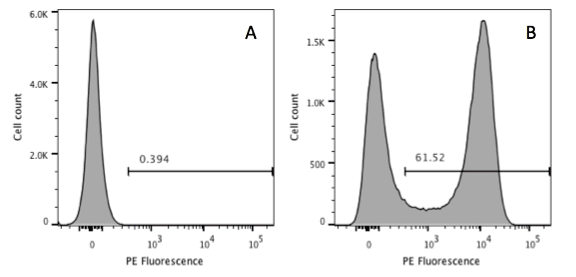

Increased autofluorescence is something to be wary of with all fixatives, and it can be particularly problematic if the target of interest is expressed only weakly. Fixation may also change the light-scattering properties of the cells, which may be important to you.

Fortunately, we’ve got a great article that explains controls you can use to mitigate autofluorescence.

Combining Fixatives: The Best of Both Worlds

It is also possible to combine fixatives, and a common way of doing this is to first fix in formaldehyde and then post-fix in alcohol. The first fixative locks everything in place in the cells, and the second fixative makes larger holes in the cell, allowing easier access for antibodies and probes.

It is also possible to use a permeabilizing agent such as Triton™ X-100 or Tween-20 as the second step.

A Few Tips for Fantastic Fixation

Now that you know a bit more about the fixative available, here are several tips to put them to good use.

Do Things In the Correct Order

The order in which you stain and fix may vary depending on the biological question being asked. Sometimes if surface and intracellular epitopes are to be examined, it is best to stain surface antigens first and then fix them. But beware, some fluorochromes are sensitive to fixation.

Fluorochromes such as phycoerythrin (PE) or allophycocyanin (APC) are large protein molecules and will be affected the same way as other proteins by the fixation, so try to avoid alcohols.

Small fluorochromes such as Alexa Fluor™ 488 or FITC are generally unaffected by whichever fixative is used.

Use Cold Solutions

Fixation should generally be done using a cold solution, as the fixation process is exothermic. The heat liberated could damage your sample and the antigens you want to detect.

Be Gentle

Cells should be vortexed gently while adding fixatives to ensure good fixative penetration and reduce cell clumping. And add at least 1 mL of the fixative solution to a cell pellet.

Perfecto: Fixatives for Preservation Summarized

We’ve looked at four fixatives for histology, seen three tips for better preservation, and gone into some background science along the way.

As long as you know the chemical effects of fixation and the types of fixative used, you can vary the process according to your needs, which can lead the way to a successful flow experiment!

It seems like a simple procedure, but there are many ways of doing this, and, as usual, there isn’t one universal way to success. So experiment and try things out!

Want some beautiful free histology posters? Check out our colorful A-Z of stains for histology and our easy controls for immunofluorescence. Download them and pin them up in your lab.

And for more histology tips and tricks, be sure to visit our Histology Hub!

Originally published November 2014. Revised and updated May 2023.