What is Peer Review?

A filter, fact-checker, and redundancy-detector all-in-one, peer review in science is the evaluation of academic work by authorities in the field before that work is published in a journal.

Its goal is to ensure that published research is original, impactful, and performed according to the standard best practices of the field.

Although forms of critical review to validate scientific information had existed before then, the peer review process as we know it today was formally established in 1731 by The Royal Society of Edinburgh as a criterion for publishing manuscripts. [1]

If you’re confused by peer review, then check out our guide now, from why peer review is important to how it works.

Why Is Peer Review in Science Important?

It Legitimizes Academic Research

Published work in a peer-reviewed journal automatically receives credibility. Having undergone editorial scrutiny and emerged intact, it is taken for granted that a peer-reviewed manuscript is “good science” and can serve as a foundation for further research.

There is hardly ever any talk of phoning the author, attempting to meet in person, or obtaining the lab notebooks to verify the data. Academics trust the peer review process.

Scientific work is one of the few pieces of knowledge in an information-overloaded world that we can be sure is vetted and scrutinized before it comes to us. [2]

It Bolsters Researchers

Not many scientists are excited when a reviewer (forever in my thoughts, Reviewer #2) gives feedback that asks them to do more experiments or leads to their paper being rejected by a journal, but this is exactly what improves the quality of our work.

Reviewers may ask researchers to repeat experiments, provide raw data, perform additional experiments, include a new figure, fix grammatical errors, and more.

After finally getting a manuscript accepted and published, the researcher has made significant improvements and is better for having gone through the critique. Did a reviewer ask you to include another control? I bet the first thought in all your future experiments is, “how many controls do I need?”

It Gives Science Credibility in a “Fake-News” World

Op-eds, blogs, and YouTube talks may attract more viewers, but they cannot boast a peer-reviewed article’s authority. The only person that has to scrutinize and approve a blog post is the blogger, and this leaves room for blind spots, bias, and a lack of credibility when held against the rigorous demands of peer review.

How Does Peer Review in Science Work?

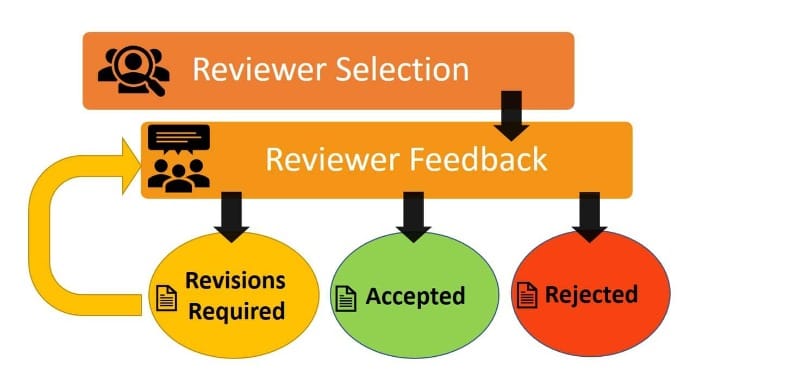

Getting a manuscript peer reviewed is already a privilege, as there are often multiple steps of pre-screening by the editors of a journal that a paper must successfully pass before the peer-review process. Figure 1 summarises the general process.

How Are Reviewers Selected?

Who gets to be the intellectual authority and validate research? None other than fellow researchers, hence the “peer” in peer review.

Reviewers must be well versed in the subject matter. Criteria for determining who is well versed differ between journals, with the high impact factor journals having the most stringent criteria.

The highest impact factor journals will check the publication history of potential reviewers for the number of publications on the field of research, how recent the publications are, and the impact factor of the publishing journals.

Here are some of the most common ways that reviewers are selected:

- Selected by the journal editor.

- Suggested by the researchers.

- Selected from the journal’s editorial board.

- Suggested by reviewers who decline an invitation to review.

Finding subject matter experts to review manuscripts is no small feat. These are typically scientists who are busy doing their own research, as “peer reviewer” is not an independent job title among scientists.

Reviewers are also doing this work as a voluntary contribution to their field, which begs the question, what do they get in return?

How Are Reviewers Compensated?

It often comes as a shock to the general public that scientists are not paid for peer review work. Reviewing manuscripts for journals is a pro bono job, a service that researchers have been giving for free for centuries.

While some view it as a duty that gatekeepers of the field should be privileged to perform, it has garnered some resentment and is even the subject of an entire Twitter blog. While there is no monetary compensation, peer reviewers get some benefits.

Reciprocity

Every scientist needs someone (read: two or three people) to review their work before publication. Participating in the peer review process, then, is a sort of barter; you scratch my back and I’ll scratch yours.

Prestige/Tenure Points

Manuscript reviews are added to CVs and help to bolster the reputation of the scientist. “Someone somewhere thought that I was an expert in this field” is sometimes compensation enough in the competitive world of academia. Good reviewers may also be invited to become journal editors, so it can also serve as professional development for the best of the best.

Early Access to Novel Research

Getting to see the latest research before it comes out is a major perk of reviewing articles in your field.

Sharpen Your Critical Thinking Skills

The more you scrutinize research, the better you get at it—for other people’s work, but also for your own.

Types of Peer Review in Science

There are different ways to go about the peer review process that vary based on the level of anonymity involved.

Single-blind

In single-blind peer review, the reviewers know the researchers’ identities, but the researchers do not know who the reviewers are. This is the most common type of peer review in academic research.

Double-blind

In double-blind peer reviews, both the authors and reviewers’ identities are protected. This is the freest of bias.

Open

The opposite of double-blind, in an open peer review, everyone knows who everyone is. The authors know from whom the feedback is coming, and the reviewers know whose work they are critiquing.

Journals like the BMJ, the EMBO Journal and the European Journal of Neuroscience take open peer review a step further by providing the reviewers’ names and comments when the manuscript is published.

Proponents of open review cite better, more thorough reviews (who’s going to submit a sloppy review when they know their name is attached to it?) and an overall more respectful, courteous process. The obvious downside is a much higher risk of bias and quid pro quo.

“Peer review” of Preprints Through Online Comments

Preprints are versions of a final manuscript before it is published and before it has gone through traditional peer review. Public commentary by peers on manuscript preprints is a new trend that is ushering in a more transparent peer-review process.

These are made available on a journal platform and are open to public scrutiny and feedback from other researchers. It is essentially the crowdsourcing of peer review.

A more traditional peer review process typically follows preprint peer review. However, having that first round of commentary gives the author quick and broad feedback that they can use to improve the quality of their manuscript before sending it to a more formal peer-review process.

Take a look at some of the pros and cons of this innovative answer to the long wait times that researchers suffer in traditional peer review here.

Does Peer Review in Science Work?

Is peer review broken? While it is the gold standard for validating research, there are several criticisms of peer review.

Slow feedback

The time between submission and publication can take months or years. These slow turnaround times are demoralizing and slow down research, especially for graduate students, postdocs, and junior faculty, who are often on a time crunch to produce publications.

Bias of reviewers

Since the scholarly criticism comes from people, it is subject to their biases. One researcher may hold dogmatically to a hypothesis that the manuscript they are reviewing attempts to refute. Good science dictates an objective eye, but this is easier said than done.

In open review, this can become a serious problem. A well-known scientist is more likely to receive favourable reviews than a less well-known scientist with the same quality of work based on their reputation.

Bias of authors

The practice of suggesting reviewers is also prone to bias. The expectation is that scientists will suggest the best experts to scrutinize their work, but they must first overcome the natural urge to suggest reviewers who will look favourably on their work.

Low reviewer expertise

As peer review in scientific publications is not compensated, it relies on the goodwill and availability of the reviewer. It also relies on the reviewer’s need to participate in the process to build a strong reputation or get tenure. This leaves out established experts who are tremendously busy and who would arguably make the best reviewers.

To combat some of these issues, journals usually choose a minimum of two reviewers and may use a third reviewer if the editors think the two reviews are wildly different.

Moreover, suggested reviewers who are deemed “too close” to the authors (e.g., are at the same institute/have published together frequently) may be rejected in case of conflicts of interest.

The Future of Peer Review

Undoubtedly, the process of peer review in science continues to be the premier gatekeeper of research integrity. It enriches researchers and improves the quality of science that is published.

Its major challenges include bias, finding expert reviewers, the slowness of the process, and ongoing debates about compensation.

Improvements include newer, diverse methods of accomplishing peer review.

As with most things, for the process of peer review in science to get better, more scientists need to get involved. Here is a way for scientists at any level do just that.

What has your experience of peer review in science been like? Let us know in the comments below.

References

- Voight ML and Hoogenboom BJ. (2012). Publishing your work in a journal: understanding the peer review process. Int J Sports Phys Ther. 7(5):452–60.

- Spier R. (2002). The history of the peer-review process. Trends Biotechnol. 20(8):357–8.