The academic publishing landscape is changing fast with the advent of pre- and post-publication peer review.

‘Publish or Perish’ is the old saying in scientific communities, and in a world of increased competition and reduced funding, all researchers are certainly feeling the pressure to publish well in the highest impact journals.

This article delves into the details of pre- and post-publication peer review and shares what these are and how you, and the wider scientific community, could benefit by getting involved.

Is Time Up for the Traditional Peer Review Process?

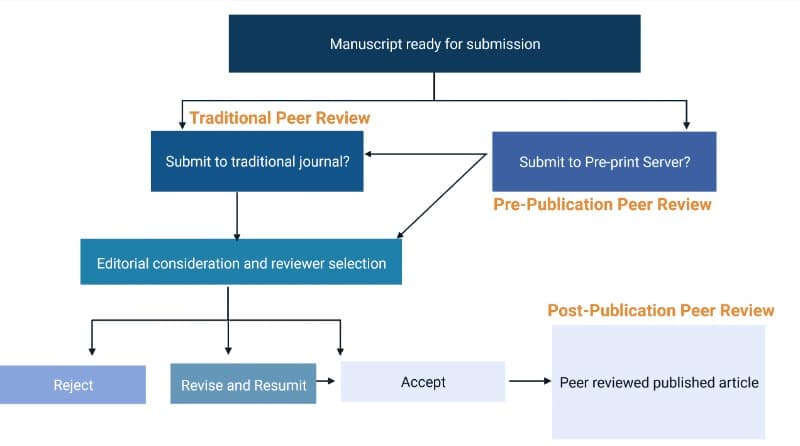

First, let’s quickly recap what the traditional peer review process looks like (Figure 1).

Most journals employ pre-publication anonymous peer review, using editorial boards to implement the review process.

These editors identify primary reviewers and shepherd the submitted article through a thorough review. Recommendations for changes are discussed with the authors, and a publication decision is made.

What Are Some of the Problems Associated with the Traditional Peer Review Process?

It is generally accepted that peer review works best if it is anonymous. However, some journals are moving to publish reviewers’ identities (if the reviewers agree). There are still problems associated with this traditional peer review, and unscrupulous scientists can take advantage of these problems. Major problems include:

- Inappropriate selection of reviewers. Authors, depending on the journal, can be permitted to suggest reviewers and alternatively request that some individuals be excluded from the review process. Although authors are required to declare conflicts of interest in selecting reviewers, this declaration may not be truthful.

- Lack of reviewer expertise.

- Traditional peer review can be a long and slow process. Many potential reviewers may be unable to review before suitable and willing reviewers are found.

Some dishonest scientists might see a way to leverage these problems associated with traditional peer review to their advantage, and issues surrounding scientific misconduct are becoming increasingly common.

Duplicating and removing gel bands, copying microscope images, cut-and-pasting two-dimensional flow cytograms, deleting outliers: no data format appears to have escaped this wave of manipulation, even extending to complete fabrication from scratch. So why is this?

The temptation for authors to cut corners (lack of repetitions, controls, non-optimal experimental designs, selective use of data, and so on) can be strong, and the way that this can lead to whole-scale, routine data manipulation is sadly obvious. This topic was covered in detail by Elisabeth Bik in a recent episode of the Microscopists.

Opportunities have even been exploited by some authors to provide completely fabricated reviewers and reviews. For instance, there was a case where an author admitted to providing fake reviewer suggestions that meant he submitted reviews on his own paper using pseudonyms!

What Is Being Done To Combat This?

The questions then become:

- How can we counteract an increasing level of fraud within scientific publications?

- What is the best and most efficient way to identify these publications and remove them, and their influence, from the published literature?

How You Can Help

1. Participate in Traditional or Pre-Publication Peer Review

Peer review doesn’t typically provide monetary compensation. But it is an important part of the academic workload since it aims to ensure that manuscripts get a high level of constructive criticism. The peer review system relies on high-quality feedback from experts in the field to allow editors to make informed and correct decisions on whether or not to publish the submitted manuscript.

You can become involved in the traditional peer review process by making sure your name is out there, and accessible for editors looking for reviewers. Make sure your contact details are listed on your lab website, for example, or include a contact email in your published papers. Let your supervisors know you’re keen to become involved in peer review, they might ask for your input if they get asked to review papers.

Alternatively, some initiatives seek to make pre-publication peer review open to all, which is becoming more and more popular. You will likely have heard of bioRxiv, the preprint server for biology. Here, biologists can post preprints of their work before they have been peer-reviewed, allowing other scientists to see, discuss, and comment on the findings immediately. In theory, this should allow dynamic and meaningful discussion between researchers.

Another related idea comes from Review Commons, which gives authors a ‘refereed preprint’. This includes the authors’ manuscript, reports from a single round of peer review, and the authors’ responses. The aim is then to enable author-directed submission of refereed preprints to affiliate journals to speed up the publication process while ensuring it remains robust.

2. Ensure Your Submitted Work is of a High Standard

It is the responsibility of all authors to be certain that the work they are putting their name to is sound. All authors should see raw data, and if there is suspect data, this should be handled before the article gets submitted.

Be aware that post-publication peer review will almost inevitably detect fraudulent activity. Second, some journals require responsibility statements indicating the roles played by all authors. If these are not specifically required, it is still good practice to include such a statement under Acknowledgments.

3. Participate in Post-Publication Peer Review

Post-publication peer review is nothing new. We have all attended scientific seminars, journal clubs, conferences, and workshops in which discussion of published work is center stage.

As journals have moved to an online electronic format, the opportunity for comment has appeared (see, for example, www.plos.org). Examples of post-publication review sites include:

- Indexing services providing post-publication reviews such as Faculty of 1000.

- PubPeer. This site provides a vigorous anonymous forum for comments directed at specific publications. It notifies authors of comments to allow their responses, opening up dialogue on published papers.

- Retraction Watch takes a more journalistic approach, providing articles that largely describe the endgame (i.e., retraction) accompanying exposure of fraud or other forms of malfeasance. Individual comments are allowed on the subjects of these articles.

There is also, of course, the avenue to go directly to the journal. In cases where readers who are experts in their field have serious concerns regarding a paper’s methods, results or conclusions, many journals offer the avenue of comments (for example, in Science, comments can be submitted concerning any article).

Directly highlighting serious issues in papers serves to inform the journal and also allows the authors to respond to the points raised. In the case of Science, anonymous comments are not permitted, which raises the issue of potential retribution in response to criticism, a particularly significant concern for early-career scientists.

The best way to appreciate these sites, of course, is simply to read them. At some point, you may become comfortable commenting (all the usual rules of internet etiquette apply, no trolling, flaming, sock-puppetry, and so on). If you are an expert, you should use your expertise to speak up about manuscripts, and not just from a negative point of view.

Why You Should Get Involved?

Aside from ensuring the high standard of published papers, peer review provides a great avenue for improving your own skills to analyze papers critically. Initially, just reading those pre or post-publication reviews posted by others will help you to get a better sense of what to look for when reviewing papers and improve your ability to think critically about published work.

For more tips on keeping track of the scientific literature, head to the Bitesize Bio Managing the Scientific Literature Hub.

Originally published in June 2015. Reviewed and updated in September 2022.