During my first year as a graduate student, one of the earliest pieces of advice that I received from a senior student in the lab was to keep detailed protocols. In fact, she had a folder of her own protocols, all of them extremely detailed and riddled with notes. When she showed me how to do an experiment, she pulled out her own protocol and gave it to me. Now, if you get handed a protocol that is so incredibly detailed and well-written, why would you need to repeat the process and write out your own? I’ll give you three reasons why.

1. You Will Make Changes to This Protocol

Even if you are doing the exact same experiment, you are still doing something completely different. Therefore, you need to write down your own notes, and perhaps changes to the protocol. For example, you may be interested in a different protein. So you’ll need to use a different percentage acrylamide gel to better resolve your protein of interest. The most you can get from someone else’s protocol is the bare minimum, the steps of the experiment. You have to fill in all the details that are specific to your experiment. In addition, you will be troubleshooting and optimizing this protocol and making it your own.

2. You Won’t Remember Everything Unless You Have Detailed Protocols

Let’s face it, our memory is not infallible. Sure, in the beginning, you only perform a handful of experiments. It won’t be hard remembering those details. But don’t forget that graduate school spans an average of 5–6 years. The number of experiments you do will continue to increase.

During my early years in graduate school, I ran a lot of luciferase assays for a couple of months, and so I wrote a detailed protocol of the experiment itself. When someone showed me how to use the plate reader to measure luciferase signals, I wrote down every single step as well. The plate reader was a dual-injection system, and you had to configure the machine specifically for your experiment. I ran assays several times a week for three or four months, and because I was doing it so much and so often, sometimes I wouldn’t need to look at the protocol. I knew exactly how much to add of which reagent, and how to run the plate reader.

That’s well and good, but then I did not have to do another luciferase assay until I was in my fifth year. By then it had been so long since I did the experiment, I had to go back and read my methods. It was a good thing I had detailed protocols, from performing the actual experiment: what the controls were, transfection conditions, and most importantly, how to use the plate reader. Otherwise I might have been re-inventing the wheel.

3. You Need to Write All of It Down Someday

Eventually, you are going to have to write about something you haven’t done since your first few months in the lab. It will be much easier the more detailed your notes and protocols are.

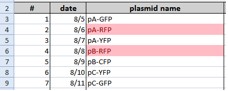

Right now, I am in the middle of writing my thesis. Having detailed protocols in a file somewhere has made writing the Materials and Methods section a lot easier and smoother. I write down exactly what I did, without flipping through all of my laboratory notebooks (all 7 of them!) for specific details. These details include plasmid vectors, primer sequences (the ones that worked!), volumes and concentration of reagents (the final ones after all that troubleshooting), density of cells plated, and so on and so forth.

In addition to writing your thesis, you will submit articles to journals. Nowadays, there is a big push for more detailed methods in your manuscript submission in response to reproducibility issues.

Also, when you are the senior student in the lab, you need to impart your knowledge to younger students. If you hand them a detailed protocol, the process will be easier.

So, why write detailed protocols?

It’s good practice, and it makes for good science.