Introducing foreign DNA into bacterial or eukaryotic cells is a common molecular biology technique. But some of the terminology involved can be confusing, particularly the three Ts: transformation, transfection, and transduction.

What do these words actually mean? To make matters worse, sometimes people use these terms interchangeably, resulting in confusion between colleagues and collaborating labs.

Here, then, is your definitive guide to the three Ts of foreign DNA insertion.

The Three Ts of Introducing Foreign DNA

Transformation and transduction (as well as conjugation) are types of horizontal gene transfer—the transmission of genetic material between organisms—that occur naturally, whereas transfection occurs only by artificial means and is carried out in a lab.

Horizontal gene transfer in nature leads to biodiversity and in the lab, it is used in gene therapy, for example. It is also the process by which antibiotic resistance arises, and is involved in a number of human diseases, however.

Let’s look at these processes for introducing foreign DNA in a bit more depth.

Transformation

Transformation is the uptake of DNA from the environment by a bacterial cell. This phenomenon occurs in nature between bacteria of the same species.

Scientists adapted transformation for the propagation of plasmid DNA, protein production, and other applications.

In research, transformation introduces recombinant plasmid DNA into competent bacterial cells that take up extracellular DNA from the environment.

Some bacterial species are naturally competent under certain environmental conditions, but competence can also be artificially induced in a laboratory setting.

This is often done using either calcium chloride or electroporation to render cell membranes permeable and enable a target plasmid to be taken up by the bacteria.

Transduction

Transduction is not a biology-specific term. The common definition of transduction is “leading through or across”.

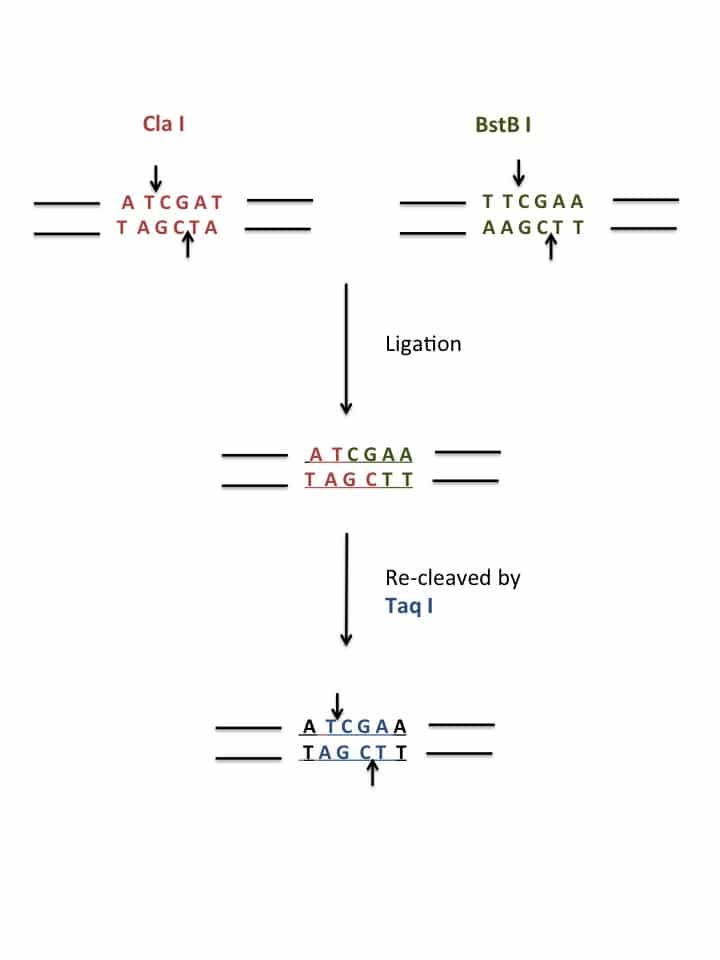

The term has been used to describe DNA transfer between bacterial cells by bacteriophages, which attach to the cell membranes of bacteria and insert their genetic material into the cell.

However, in current research, transduction also refers to the infection of mammalian cells with a viral vector.

“Transduction” was first used to describe bacterial gene transfer back in the 1950s, decades before the creation of viral vectors.

It’s possible that the word has been co-opted to prevent confusion, as “transfection” doesn’t distinguish between the introduction of nucleic acid or viral particles into a cell.

“Transduction” is mostly used to describe the introduction of recombinant viral vector particles into target cells, while “infection” refers to natural infections of humans or animals with wild-type viruses.

There are no universally accepted differences between these two terms (a quick Google search uncovers all kinds of online debate). They are mostly used as a convenient way to differentiate between two biological mechanisms.

Transfection

Transfection is the forced introduction of small molecules such as DNA, RNA, or antibodies into eukaryotic cells. Just to make life confusing, “transfection” also refers to the introduction of bacteriophages into bacterial cells. But for the purpose of this article, we will focus on eukaryotic cells.

There are two types of transfection: transient and stable. Check out our article on the principles and mechanisms of mammalian cell transfection for more information.

Common transfection methods include calcium phosphate, cationic polymers (such as PEI), magnetic beads, electroporation, and commercial lipid-based reagents such as Lipofectamine and FuGENE. Check out our transfection toolkit for more information!

Clear as Mud?

In some ways, the “Three Ts” terminology for introducing foreign DNA is arbitrary. Terms used for bacterial studies back in the mid-twentieth century are now used for other applications, and the development of new molecular techniques has required changes to our vocabulary.

Rather than technically correct definitions, these terms are now used to conveniently describe different biological research processes.

The main consideration is making sure that all lab members and collaborators (if possible) are on the same page when it comes to terminology about introducing foreign DNA. This will prevent widespread confusion and inaccuracies during research and publication.

Originally published January 24, 2017. Reviewed and updated August 2021.