After a very naïve start in flow cytometry thinking that published protocols will work without fault – needless to say, that did not work out in my favor – I realize now that following a few simple steps can go a long way, and will undoubtedly save you time in the end.

So, here are 10 steps that you can take to help you tackle your own flow experiments.

1. Do your research

Before you even start, research as many protocols as you can find (without the preface that you can just follow them to the ‘T’). If you can find some that include both your marker and cell type then they could be a good starting point on which to base your experiment. Although, even if you do find one that seems an exact replica of what you want, you should still do the following steps.

2. Take the time to titrate

Titration is always an important step in any type of experiment. For flow cytometry, you will need to do some preliminary titrations of primary and secondary antibodies before you start. Antibody titrations will help you achieve good quality data and save you money: recommendations are often higher than needed.

You should also titrate the concentration of cells in the experiment.

3. Be in control

ALWAYS use controls. This is probably one of the most important points, and there are a number of different controls you can use. You should always try to have a negative or unstained control as well as single-color controls for each color you will use. FMO (fluorescence minus one) controls, which contain all markers except the one of interest, should be included in multicolor sorts.

4. Know your colors

Make sure that the colors you have chosen can be detected by your machine, and that they will work together. You will need to take a look at the excitation and emission spectra of the dyes/conjugated antibodies you plan on using. Obviously, it is best if they don’t overlap, however, if they do there’s always compensation. This becomes more important as the number of fluorophores increases and overlap can’t be avoided. You can use this useful tool to determine the excitation and emission for many different fluorophores at once.

5. Know your limits

Some markers and assays require fixation and/or permeabilization, which depending on what you want to do next with your cells, may not be possible.

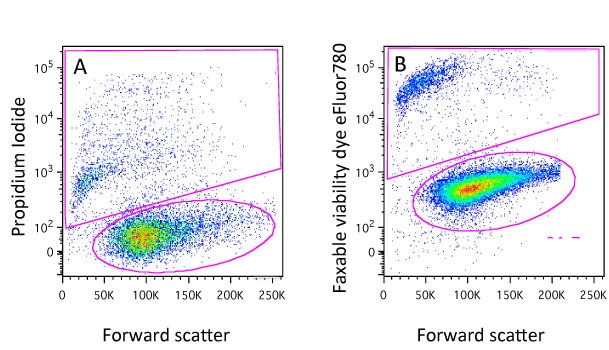

6. Prep your cells correctly

Make sure there are no clumps in your cell suspension as this can skew your results, especially if you are sorting on size. If your cells are sticky and tend to form clumps there are a few things you can add to your cells, (e.g. EDTA or DNAse), but be careful in your choice as they could also affect cell properties.

7. Plan your next steps

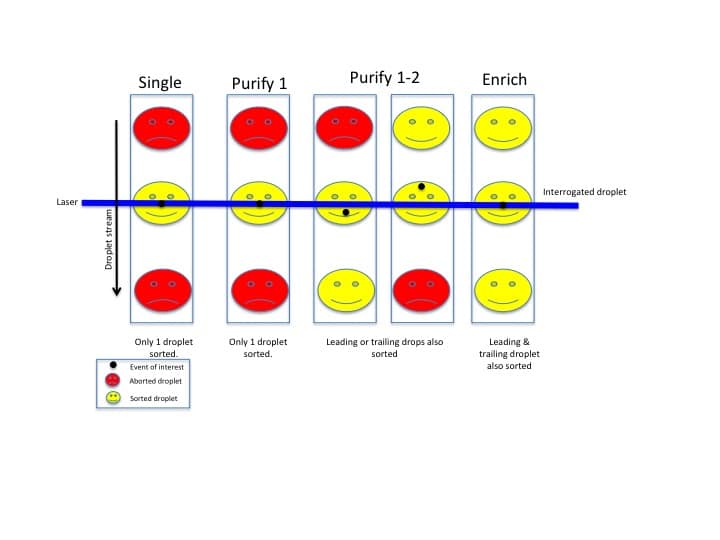

Figure out how many cells you will need to do the next part of your experiment beforehand. For example, if you want to extract RNA for a microarray, then you may need a minimum number of cells for a good yield. Depending on the concentration of the cells of interest in the parent population, this could take a rather long time (hours for some types of stem cell). You might have a decision to make: sort your cells for hours and possibly cause stress to your cells, or sort faster and risk getting a less pure population, or you can split it into a few experiments and pool your RNA.

8. Don’t forget about the buffer

The buffer your cells are in can interfere with laser detection – e.g., phenol red will increase background fluorescence. It is therefore better to sort in a media without phenol red – you can culture and stain them in your specific media, swap it out for a phenol red-free media for the sorting experiment and then collect them in the original media.

9. Plan ahead!

Work out all the experimental parameters before the day. When you are doing flow, especially for the first time, there may be many variables e.g., titrations, controls, cell number. This means many samples, which can be confusing. So working out a plan of attack in advance can save a lot of time, confusion, and could possibly save your experiment.

10. Don’t be afraid of flow cytometrists

Finally, communicate with your flow cytometry facility. They will undoubtedly have good tips on what to do and what not to do. They have also seen many different experiments come through their doors and may have some knowledge about your specific requirements. So don’t hesitate to ask questions – it may save you a lot of time.

Hopefully these tips will prevent you from being as naïve as I was before I started flow cytometry.

Good luck!