Summertime… The birds are singing, the trees are growing. Your tissue culture has sprouted yeast contamination, your yeast culture is happily growing bacteria. Your bacterial culture was growing calmly and predictably, dividing every twenty minutes, but suddenly its optical density has dropped, and it’s full of some sort of filaments and clumps.

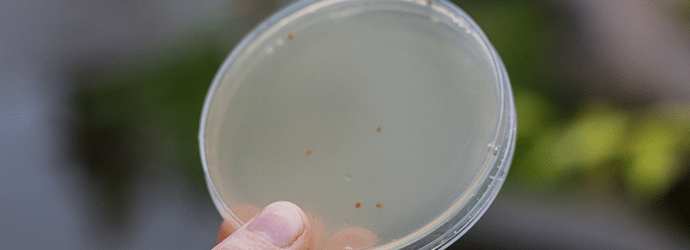

Or you did a transformation, and the usually round colonies look like somebody has taken a bite out of them, and there are circular ‘no growth’ areas on the plate.

Condolences, you have a bacteria eater, aka: phage contamination. And it will not disappear unless you do something about it.

Here are some tips for getting rid of phage:

1) If you can throw out the contaminated culture, do it; but don’t just put some vircon into it, autoclave the culture to kill the phage.

2) Discard all of the solutions you used to prepare the culture.

3) Clean the shaker, your bench and other surfaces which might have contacted the contaminated culture, with ethanol. If possible, use a UV lamp overnight. Dust is phage heaven – they can survive for many years in a dry environment – so be thorough.

4) Clean your pipettes with a strong disinfectant.

5) Put all your flasks (and all of your glassware, ideally) through the oven at 180°C.

6) Use new stoppers – the old wet ones (especially foam bungs) can be literally saturated with phage.

7) Do not open your flasks during culture growth – you can control the air flow on your bench with a Bunsen burner, but it is never safe to open flasks for a “peek” while they are still in the incubator.

But what if contaminated culture is really unique and precious – the half-eaten colony is a clone you’ve been making for the last half a year or a strain you’ve been sent from a lab in Australia?

Phage, like E. coli, goes through growth phases: infection, followed by multiplication, cell lysis and re-infection. The vigorous mixing used for liquid cultures promotes phage reinfection, so it is better to use plates (freshly made under aseptic conditions) to isolate uninfected bacteria from your culture. Repeatedly streak your strain for single colonies.

The way to prevent reinfection is to grow your culture really slowly, at 20°C – slow bacterial metabolism means slow phage growth, and the tortoise will not catch up with Achilles. If you are getting repeated contamination, the air conditioning filters need to be checked/replaced.

If after all the precautions you’ve taken, your bacterial culture still combusts spontaneously, the infection may be not external, but internal. Drawing a parallel with human disease, your infection may be not acute, but chronic. The bacterial strain may be lysogenic, e.g. contain phage DNA integrated in the chromosome or as a plasmid. This ‘prophage’ is induced by high temperature or just spontaneously, killing cells with a vengeance. In this case, you need to select a phage-resistant mutant by plating the survivors.

If this doesn’t help, pray to forefathers of molecular biology, bacteriophage researchers Max Delbrück, Alfred Hershey and Salvador Luria.

Further reading:

Los M, Czyz A, Sell E, Wegrzyn A, Neubauer P, Wegrzyn G

What are your tips for avoiding phage contamination?