Research is a snare.

Noble aims—curing cancer, reversing the aging process, solving world hunger, and getting a beneficial new pill to market—get us out of bed.

But these goals are so savagely remote that we have to imagine we are closer than we are and that today’s transferal of clear liquids from one vial to another gets us notably closer.

A sustained effort of imagination, motivation, and inspiration keeps our heads up. And we are more likely to succeed if we keep our ideas, approaches, and attitude from stagnating. Plus, random unrelated skills can benefit lab work.

But where to search for all this?

We don’t have the answer, but we have some great suggestions! Here are ten fun hobbies for scientists that can help boost your research and give you much-needed downtime.

1. Weightlifting

As you’ll be aware, working in a lab is weirdly physical.

Ever taken delivery of and installed a new piece of kit? Ever had to drag a heavy instrument to make room for something new? Centrifuges, fridges, chromatographs, transilluminators—none of them are light!

And doing the stores run to get all the months’ consumables for your lab doubtless involves hefting boxes upon boxes of stuff.

Plus, you’re on your feet most days.

Weightlifting will make all of these chores more manageable. It’s also great at venting frustration and destressing.

You could buy a set of cheap free weights and keep them at home or join a gym. Stick with it, and you’ll acquire two other assets: discipline and commitment.

2. Yoga

Crouching, craning, stooping, straining.

The stuff we need in the lab is usually on the floor, on the top shelf, and is too small and difficult to see.

What’s less ergonomic and back-friendly than loading an SDS-PAGE gel? How do your shoulders feel after filling your 96-well plates?

On a hard day, I got in from the lab feeling like I had been in a fight.

To look after your joints and posture, why not take up yoga?

Being more supple will improve your overall lab fitness, protect you from poor posture and repetitive strain injuries, and make you feel better.

It can be a social activity that gets you outside. Or you can follow an online class, solo, indoors, if that’s more your style.

And if you do a stress-busting activity like running or weightlifting, as suggested, it’s wise to stretch too to stop you from becoming outrageously taught!

3. Knitting, Crocheting, or Cross Stitch

Science is fiddly, and good hand-eye coordination and dexterity help avoid gross errors and subtly make your research more reliable.

Some good examples of tasks it helps with include:

- Handling precious liquid samples.

- Knocking over and breaking expensive items.

- Pipetting out assays.

- Preparing grids for cryo-EM.

- Preparing histology slides.

Knitting, crocheting, and cross-stitching are stress-free, chilled-out ways to improve your dexterity.

And the great thing is you have something you can give away at the end! You could even create science-themed makes to adorn your lab or home (Figure 1).

You could make a throw or a hat. You can even knit your own dog (I have one—he’s a beauty.)

If you’d prefer some biology and lab-related crochet patterns, our favorites include a micropipette, a eukaryotic cell mini pillow, and a collection of adorable microbes!

4. Drawing or Painting

Painting could be your synaesthetic approach to your next experimental design.

Who’s to say pretty patterns cannot inspire actions and abstract relationships are not expressible in colors? Check out the artwork of David Goodsell and Anna Liber Lewis and see what you think.

It could also unlock creative ways to present data, and at the very least, it stops you from thinking about science for a bit—which is when the most helpful ideas seem to pop into your head.

Plus, it will help combat perfectionism, which eats unnecessarily into our time, drags us down, and discourages trying new things.

You don’t have to stand at an easel and try a hyper-realistic watercolor. You could paint an abstract t-shirt for your next festival, a teapot, or some rocks!

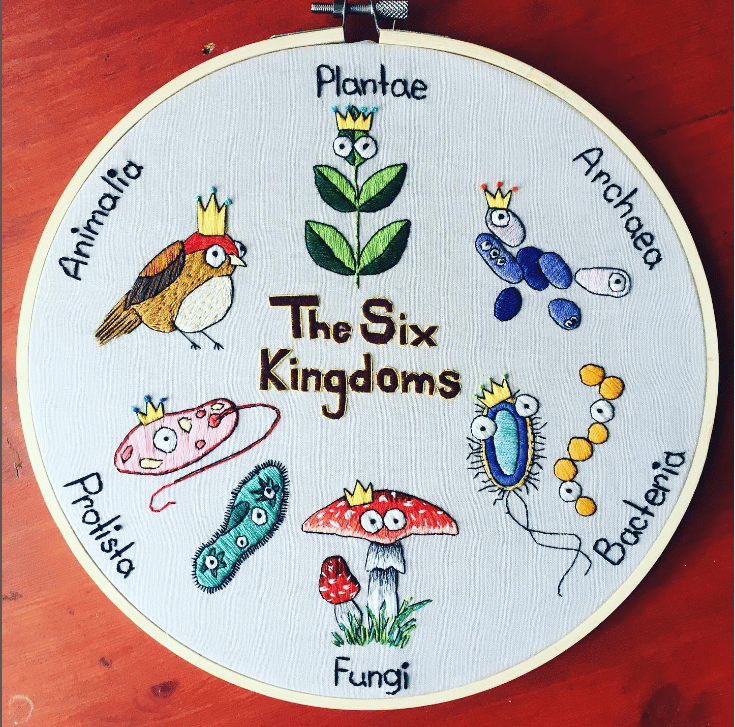

Here are some rocks I painted to destress during a difficult time during my Ph.D. course. I then went with a friend and scattered them in the wild like Horcruxes, which was an excuse to get out in the sun for a bit (Figure 2).

Yes, they always looked dodgy and are worse now because they have spent five years in a plant pot. But you can tell what they are!

5. Boardgaming

Sometimes, your data are extremely complex, and you’ve got to figure out what it means and how it fits together.

Sometimes, you need to do mental arithmetic.

Sometimes, people don’t have your interests at heart and are out to get one over on you.

Do you know what can help with all of these? Board games.

You can have a good laugh, test your critical thinking, and get better at doing things quickly (and secretly).

Don’t know where to start? Here’s a list of some of our favorites:

- Like birds? Wingspan is a stunning game with beautiful artwork and cute little egg counters.

- If building cities is more your thing, Carcassonne is a great game that you can play either in a relaxed fashion or ruthlessly by blocking builds and taking over cities.

- Looking for something cooperative? Why not work with your mates to defeat a global outbreak in Pandemic?

6. Performing Arts

Ah, lab talks.

We all have to get up and talk in front of a live audience at some stage. And we all hate it.

What adds to the problem? The entire scientific approach depends on a skeptical inquisition of new ideas. So your audience is usually against you. Honorable mention here to all the legend-on-their-lunch break academics who aren’t skeptics but just difficult.

Performing arts can help us overcome our fear of speaking to crowds in a gentler, more welcoming setting!

You could join an amateur dramatics society. You could join a choir. You could join a band and do open mic nights!

All of these are fun ways to help you handle the pressure of speaking to potentially hundreds of hard-nosed scientists.

And there’s nothing quite like that moment when you realize no one cares that you look a bit of a fool—no matter how you feel.

7. Reading

Our ideas are like nebulae.

Precise words help capture and articulate them accurately. Clumsy words erode their meaning.

And a significant proportion of a scientist’s time is spent conveying ideas. Think of:

- Formulating a hypothesis.

- Convincing your supervisor that it’s sensible and worth investigating.

- Writing the grant application to get the money to investigate it.

- Defending your ideas at interim lab meetings.

- Publishing your conclusions.

All require compelling and clear language, but the audience is different in each example.

To be successful, you must tailor your language. How can you do this without a good set of words and imagery to choose from?

So read as much as you have the appetite for it. Whether it’s fiction, nonfiction, scientific, or otherwise. It will make you sharper and more articulate.

For a thoughtful take on how to use words to encapsulate our thoughts and bad habits to avoid, read Politics and the English Language, [1] a celebrated essay written by George Orwell.

8. Subscribe to a Popular Science Magazine

For all the ways our daily lab work fails to relate to anything consequential, we might as well do our work in the vacuum of space.

For example, preparing 1 M tris–HCl has as much to do with curing Alzheimer’s disease as the heavenly bodies do with one another.

The disconnect can be jarring and discouraging.

But you can get inspired and keep the world-changing humanitarian and economic benefits of science in focus by subscribing to a quality magazine like National Geographic or New Scientist.

You’ll remind yourself that your occupation improves society.

You’ll read about astounding technology in neighboring and distant disciplines, which in turn encourages collaboration and a holistic approach to the branches of science that can often seem Cartesian in their isolation.

And you don’t have to read them cover to cover to enjoy them. I’m a fan of the infographics published in Nat Geo that make stupendously large amounts of data comprehensible.

9. Writing, Blogging, or Poetry

At some stage, you’ve got to commit your results to writing. It doesn’t have to be The Iliad, but it has to be halfway decent.

Seeing all the red ink when you get interim feedback can leave you feeling despondent too.

Better to get some practice in while the stakes are low, right?

You could write for a blog, write for Bitesize Bio (get in touch), start keeping a journal, or have a go at writing poetry.

Keep it simple and keep it for you if you want, and you’ll slowly improve at making your point and writing for different audiences.

10. Gardening

The cleverest materials scientist I know is an avid gardener with an allotment. It makes sense; he researches clays and eggshells.

Gardening can teach you patience, make you better at dealing with frustration (when your tomatoes get blight and die), and reduce stress levels (when your tomatoes flourish). [2]

You’ll set long-term goals and deal with things beyond your control.

What’s not to like?

It’s not for everyone—you need a garden for starters.

But if you work at a University, there are probably community gardens and greenhouses you can volunteer at. So be sure to check.

Get Inspired

Don’t believe serious scientists have time for hobbies? Not so!

Kary Mullis, the inventor of PCR, was an avid surfer.

And the agronomist, Nobel Peace Prize winner, and GMO pioneer Norman Borlaug was on his college wrestling team at the University of Minnesota.

The belief that you must chain yourself to your lab and that only actions conducted inside it qualify as meaningful is misguided and probably a form of abuse.

Fun Hobbies for Scientists Summarized

There’s an assortment of fun hobbies for scientists that can boost your research through inspiration, creativity, fitness, and articulacy.

They are not to everyone’s taste. Of the options on the list, I do 1, 4, 7, 8, and 9. But I once tried amateur dramatics, loathed it, and quit immediately. I also can’t stand most board games.

Remember, no one’s forcing you to do anything.

Nor must you go into things thinking: “this is going to make a better scientist.” It’s probably better not to do so, so you engage with everything sincerely and at its own level.

The benefits might come way off in the future.

What do you do to stay engaged and inspired with your work? Let us know in the comments section below!

References

- The Orwell Foundation, Politics and the English Language by Orwell, George. Accessed January 2023

- Chalmin-Pui et al. (2021) Why garden? – Attitudes and the perceived health benefits of home gardening. Cities 112:103118