Are you looking to improve your lab work, publication record, and grant success rate? Implementing feedback can help scientists do all that and it’s great for your personal development.

Having an open mind and a good attitude when receiving feedback on your performance is fundamental to personal and professional progress.

Feedback can be uncomfortable—for both the person giving it and the person receiving it—but in this article, we’ll give you some tips to get the most out of any feedback you do receive.

We’ll outline what feedback for scientists is, where it should come from, and how to give feedback to others. We’ll also tackle how to receive feedback graciously.

What is Feedback For Scientists?

You’ve seen the movie: a world crisis requires a massive scientific breakthrough. A passionate yet solitary scientist toils away in the lab, unfazed by countless failures and determined to find the solution.

Working endlessly to solve the problem, these scientists have a seemingly random breakthrough idea that works, and they save humanity at the eleventh hour. Hurray!

If only solving real scientific problems was as simple as locking oneself in the lab. In reality, we all lean heavily on the input and direction of others to navigate the complicated and multifaceted challenges of scientific research.

Science is rarely conducted in a bubble—even if you do most of your work solo, you’ll still need to present your findings to others and receive feedback from the community.

Effective feedback is a mechanism by which a recipient receives information or critique on actions taken or progress toward an objective.

Feedback for scientists can be formal or informal, written or verbal, but the goal of constructive feedback is always to adjust or improve behaviors.

So, you might receive feedback on improving your scientific writing or developing a better technique for a job in the lab. When provided with thought and care, feedback provides opportunities for individuals and groups to grow and excel.

Why is Feedback Important in Research?

There are myriad benefits to receiving feedback. Scientists who regularly seek high-quality feedback

- waste less of their personal energy and fewer lab resources;

- improve overall personal performance, as demonstrated in a multitude of studies;

- report feeling more engaged and have higher job satisfaction;

- are associated with embodying a “growth mindset“, which is associated with higher indicators of success in STEM disciplines, including resilience and creativity;

- encourage a work culture of receptiveness and personal improvement.

With all that said, it can be really challenging to request feedback and take it graciously. Thankfully, giving and receiving feedback is like working a muscle. The more you exercise feedback, the easier this skill comes!

Where Should Feedback for Scientists Come From?

To get the most bang for your buck in getting feedback, you should actively seek it from a variety of sources.

Your PI and Committee

In a science career, you constantly interface with supervisors to receive direction on your projects. But don’t expect to be patted on the back or mollycoddled!

PIs and committees can be brutal with their feedback and may request many changes to any given piece of work. While this can turn into a long and iterative process, there are two straightforward ways to prevent some of that negative feedback:

- Set up regular and recurring meetings with your PI to concisely communicate your results and take notes on requests for future work.

- Work ahead when writing papers or preparing presentations, providing drafts to all members of your committee before due dates.

If you don’t get as much feedback from supervisors as you would like or feel that they are being especially harsh or unhelpful, check out our article on maintaining good communication with your advisor.

Remember that it is their job to help you grow by providing direction and expectations to invest in your success.

Reviewers

After laboring over writing up your results and preparing meticulous figures, you submit your paper to a journal for peer review. Even if your reviewers accept your paper for publication, you may have to address reviewer comments and make major or minor revisions.

Even if you don’t agree with all the comments raised, you must still address all critiques carefully. Some journals give you just one chance to address reviewer feedback, so respond to feedback using these tips:

- Reply to each question and comment thoughtfully, in a detailed, and organized manner. Provide point-by-point responses that address each reviewer.

- When including additional data or experiments, provide a summary of those results and reference where they are included.

- If two reviewers give conflicting feedback, ask an editor and trusted colleagues for guidance to address the issues.

- If you decide not to change part of your paper based on a comment, provide additional evidence or justification for why this isn’t relevant.#

- Always remember to include a thank-you to reviewers for their input!

Peers in the Lab

Getting feedback from your colleagues improves communication channels and gets issues out in the open to be resolved.

When working in a shared lab environment, there are bound to be times when issues arise, and tensions fly high:

- sharing instruments fairly;

- keeping the lab tidy;

- ensuring the lab is stocked with the materials needed;

- making sure communal reagents are correctly prepared.

It can be intimidating to confront a peer with a concern about their work, but it’s in the entire group’s best interest to be transparent when it comes to these activities.

To resolve minor problems before they escalate into major issues, foster lab cooperation by being open to feedback about your presence at the bench and being kind when bringing up minor concerns.

Consider having a standing “check-in” agenda item for group meetings to ensure that everyone has a chance to provide input about the day-to-day activities in your lab.

Direct Reports

Most people feel uncomfortable providing unsolicited feedback to their managers, and you may need to schedule sessions for drawing feedback from your team.

A great idea to get direct reports to open up about your performance as a leader is to ask “yes” or “no” questions, such as:

- “Is the frequency of our lab meetings too high?”

- “Do you feel that you know what experiments need to be done in the next week? Month? Quarter?”

- “Do you feel that I am providing you with enough opportunities to network with others?”

- “Do you typically prefer getting written communication via instant chat or email?”

- “Am I helping you grow professionally and giving you chances to try new things?”

If you’re still not getting the feedback you’d like, you could try collecting it via a comments box or similar so that your team can give feedback anonymously.

Gaining employees’ perspective is a win–win, since allowing for upward feedback increases job satisfaction and increases the likelihood that team members come to you with ideas for improvement.

How to Ask For and Receive Feedback

Now that we know where feedback should come from, let’s look at ways to get high-quality feedback.

Start With Your Attitude

I can’t emphasize enough that to best receive feedback of any kind, you must be wholly and openly receptive to input. Remember, without challenge, there is no growth!

It can be stressful to ask someone to take a critical look at a presentation that you may already be nervous about giving, for instance, but wouldn’t you be more upset if no one in your audience learns from it or finds it confusing?

Come Armed with Questions

To get the most out of a feedback session, know what you are looking for feedback on before the meeting. This preparation allows for targeted, timely, and clear feedback.

Here’s some example language:

- “I sent the entire presentation for your review, but I’m most interested in hearing your thoughts on the figures in slides 5–8 and whether or not they highlight my takeaway.”

- “Will exploring this proposed avenue in my research lead to publishable results by June?”

- “Do you think that the edits I’ve made to this section help to provide enough background for a reader outside our field?”

Disarm Feedback When It’s Not Given Well

If you disagree with the feedback you’re receiving, never fear—it is possible to set the tone for calm and respectful conversation.

- Listen actively and don’t interrupt. Allow the person to finish their point before responding with your perspective on the issue.

- Take a moment or a breath if necessary—especially if feedback is emotionally charged.

- Try to home in on a solution that makes sense to both parties, bringing up justified decision-making reasoning.

- If you are still unable to accept feedback or it hits you the wrong way, use language that acknowledges the feedback but defers immediate action.

- Politely noting that you will look further into the proposed change allows the feedback giver to feel heard while allowing you not to implement the suggestion immediately.

For especially vague feedback that doesn’t give you a clear direction, you can employ “drill-down” questioning. This might take the form of the following:

- Reviewer: “I don’t think this figure belongs in this section. It doesn’t seem to help the reader.”

- You: “That’s interesting, I hadn’t thought about it from that perspective. What do you think makes it challenging for the reader?”

- Reviewer: “It’s very information dense—I think it is confusing as is.”

- You: “I see—do you think there’s too much text in the caption or too much going on in the figure itself? Do you think it could be split into multiple figures?”

- Reviewer: “Well, yeah, the caption is really long. Maybe the whole figure could be split into two in order to break it up a bit.”

- You: “Interesting! What are your thoughts on breaking it up this way?”

You get the idea! Drill-down questioning is where you (positively and kindly) continue to ask questions until you get the answers you need to understand how to address feedback precisely.

Get a Holistic Picture

Just like you use multiple replicates to get an average and more accurate picture of a sample you’re analyzing, get multiple perspectives when it comes to feedback.

If one of your lab mates disagrees with how you are setting up an experiment, but your PI and entire committee affirm your decision, odds are you are on the right track!

Take Notes

Don’t forget to take notes during feedback sessions when it seems appropriate. Taking notes has two tangible benefits:

- You can review and summarize your notes at the end of a feedback session to make sure you understood the feedback correctly.

- You can refer to them later to ensure you’re implementing suggestions.

This also helps to avoid receiving repeated feedback. After all, it’s incredibly disheartening to receive the same feedback twice.

For example, if feedback relates to some form of writing, keep a list of feedback points in a file on your computer, and refer to it each time you submit a piece of work.

Always Follow Up

Letting someone know how you’ve implemented their advice is incredibly satisfying for both parties and encourages further collaboration.

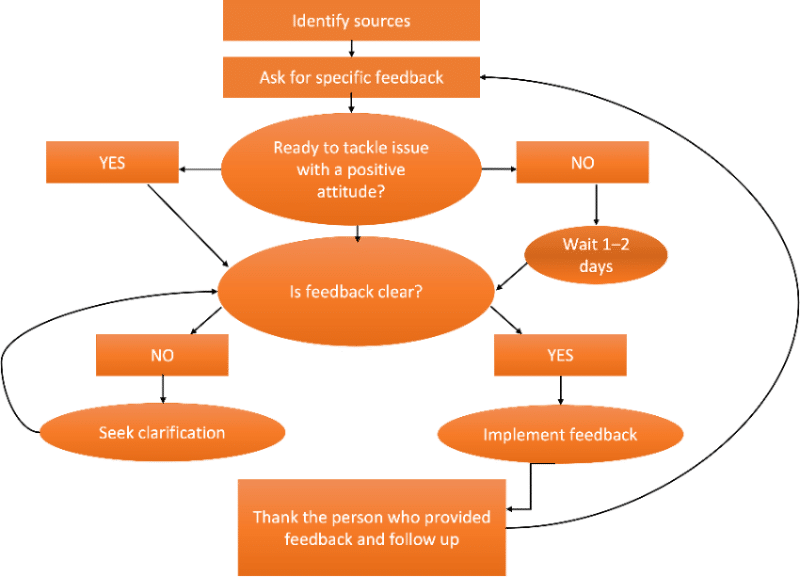

Send thanks along with evidence of changes made, such as manuscript edits or a new experiment in progress. It’s also a good idea to communicate your openness to continual feedback (see Figure 1)!

How to Give Feedback

Handling feedback is one thing, but giving it to others is entirely different. Effective scientific leaders are skilled at providing feedback without coming off as judgmental or overly critical. Consider the following to help guide you when providing feedback to others.

Below are some tips and examples of well-delivered and not-so-well-delivered feedback.

- Ensure the space you are providing feedback in is private so that the other person doesn’t feel embarrassed in front of others.

- Bad example: Group meeting with your shared PI.

- Good example: During a coffee break.

- Avoid “you” statements and accusations.

- Bad example: “You haven’t analyzed your data enough!”

- Good example: “I felt that this needed more in-depth analysis to make your work shine.”

- Use a sandwich technique to soften the blow of negative feedback.

- Bad example: “You’re hogging the lab space!”

- Good example: “You’ve been putting in some long hours and working hard! Could you make time in between experiments to tidy up? It’s been getting crowded and I’m having trouble keeping up with you!”

- Explain your perspective as an outsider.

- Bad example: “This paragraph is completely out of context!”

- Good example: “As a reader, I was focused on the extraction results from the previous section but found it difficult to switch gears to thinking about how they tie into the model. Could you add a transition sentence to help the reader make that mental shift?”

- Be timely so that your recipient understands why you are providing feedback and can implement it as soon as possible.

- Bad example: Giving a trainee suggested edits the week before a deadline.

- Good example: Proactively letting your trainee know you are available for revisions when they begin drafting the document.

- Explain how current behavior affects other parts of people’s work.

- Bad example: “You didn’t book the HPLC calendar yesterday.”

- Good example: “I had to postpone an important HPLC run that was critical to my work since the instrument was being used during my time slot. Can you double check the calendar before starting a run in the future?”

- Suggest solutions. No one likes open-ended feedback, and offering tangible suggestions for improvement makes it more likely your feedback is well received.

- Bad example: “It doesn’t seem like your results are conclusive and you probably need more data.”

- Good example: “I was thinking you could run this proteolytic assay. I actually know someone in the neighboring lab who runs it almost every week…”

Taking and Giving Feedback Summed Up

In short, receiving and giving feedback can be tricky, but if implemented effectively, feedback can improve all aspects of your scientific career. It’s critical that you seek feedback, learn how to implement it, and take the time and energy to give effective feedback to others.

Do you have any additional tips for giving or receiving feedback for scientists? Have you encountered situations where feedback has been given very well or poorly? Share your experience with us in the comments below!