Slide one? Tossed. Slide two? Tossed. Slide three? No good either. Ten slides later and you still don’t have a fantastic, easy to read slide. Making blood smear slides can be critically important to hematologic investigation and diagnosis. They can be a useful tool to assess everything from white blood cell disorders, such as leukemias, to various types of acquired or congenital anemias, to broader organ issues like liver or kidney disease. However, the effectiveness and accuracy of that interpretation depend on the quality of the slide. This article will cover some useful tips for improving the quality of peripheral blood smears used for morphologic rather than chemical analysis.

The Ideal Blood Smear

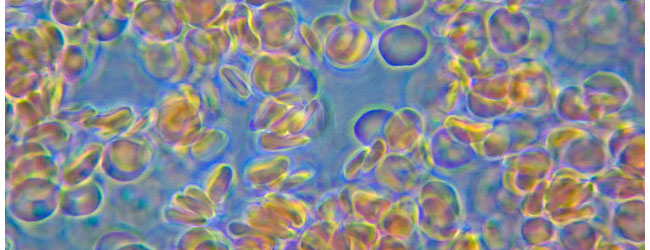

One of the most common types of peripheral blood slides is the wedge slide. An ideal slide is neither too thin nor too thick. It should end about two-thirds to three-fourths of the way down the slide. The end of the smear should be thin enough that it has a rainbow-like reflectiveness about it, and there should be no streaks at the very edge. Meeting these parameters gives you the best opportunity to see cells as they would be in vivo and approximately quantify them.

Slide Making Basics

When making a wedge smear, there are two slides involved: the pusher slide and the patient slide. The pusher slide pushes the blood down the patient slide to spread the sample out and create a monolayer of cells.

To make your slide, there are just four steps to follow:

- Place a drop of blood on the patient slide near the frosted edge.

- Place either the long or the short edge of the pusher slide just in front of the blood drop, holding it at an approximately 30-degree angle from the patient slide.

- Push the edge of the pusher slide into the blood drop so that it spreads out completely along the pusher slide.

- Push the blood down the patient slide with the pusher slide.

With every slide you make, there are a couple of things that you should always do to ensure the best quality. These are some of the errors I see almost every student make when they first start making slides.

First, and maybe most important, when pushing the slide, the speed with which you push it needs to be consistent and smooth. Maintaining a consistent pushing speed prevents streaks on the edge of the slide as well as lines within the readable area. Simply trusting in yourself can help improve your slide-making skills. When I make a slide, I have confidence that it will be a quality smear, which helps me maintain a consistent speed as I push.

Second, let the blood spread all the way out before you start to push. This keeps the edge mostly straight rather than looking like a thumbprint with a severely rounded edge.

Holding the Slides

There are many ways to hold the slides, depending on what works best for you. Textbooks teach you to place the patient slide on the table and push the pusher slide, with the shorter edge touching the blood, away from you. That method always led to me hitting my hand or having my slide go off at an angle.

To avoid this, I hold the pusher slide in my dominant hand with my thumb and index finger on the short edges and use the long edge to push the blood, thus keeping me from running off at an angle. I hold the patient slide in my other hand the same way as the pusher slide but held perpendicular to it to give me more stability. In the end, all that matters is that the pusher slide edge is flat against the patient slide. Try different ways of holding the slides to see which feels best for you.

Further Changes You Can Make

Once you know how you want to hold the slides, there are a few adjustments you can make as you push the slide, depending on the quality of blood:

- Pusher slide speed.

- Amount of blood.

- Pusher slide angle.

In my experience, the main parameter that affects how the blood pushes is the hematocrit level. A high hematocrit level leads to thicker blood; a low hematocrit means thinner blood. The thickness of the blood affects how quickly it spreads against the pusher slide and how far down the slide it pushes. You can control for this variation by adjusting the items listed above. When I make a slide, I know what adjustments to make as soon as I see the blood spread against the pusher slide. Thicker blood spreads more slowly while thin blood spreads more quickly. I made a chart to highlight the changes you can make.

| Parameter | High hematocrit (thicker) | Low hematocrit (thinner) |

|---|---|---|

| Pusher slide speed | Slower | Faster |

| Amount of blood | More | Less |

| Pusher slide angle | Decrease (<30°) | Increase (>30°) |

Knowing the patient’s age and health status can help you determine the best way to make your slide.

Working with Blood with High Hematocrit Levels

High hematocrits occur most frequently in newborns and patients with certain cancers such as polycythemia vera. You must push more slowly to ensure that the blood spreads far enough down the slide. Using a larger drop size can help get enough blood to spread the desired two-thirds to three-fourths of the length of the slide. You can also change the angle of the pusher slide. Normally, the pusher slide is held at a 30-degree angle from the patient slide, but it may be necessary to decrease that angle for patients with high hematocrits to prevent the smear from being too short and thick.

Working with Blood with Low Hematocrit Levels

Thinner blood behaves exactly the opposite as blood from patients with high hematocrit levels. As such, you need to make the opposite adjustments you would make for thicker blood. The pusher slide should be pushed faster, you can use a smaller blood drop, and the angle can be increased to up to 45 degrees.

As with everything, practice makes perfect. Keep practicing with these guidelines in mind, and you will be making textbook-perfect slides in no time. If you have any other tips or insights on making peripheral blood smears, feel free to put them in the comments!