Tiny, furry, spinning around a wheel—few creatures are as endearing as the lab mouse. Trying to obtain reproductive success with them, however, can leave you spinning your own wheels. Why is it that what works so well for the animal facility staff, or experienced technician, seems to be beyond your reach? After all, mice have great fecundity. So much so, that you assume that when you put Bruce and Sally in the same cage, and come back the next day, you should be assured of a hearty litter of pups in 20ish days. Well, sometimes, but not always.

Thankfully, it’s not up to a random stroke of luck, but rather sound breeding techniques which literature searches and years of experience will reveal. Here, I’ve listed my top 10 tips for successfully mating mice, specifically the strain I work with—C57BL/6J.

- If you house female mice together they will synchronize their estrus cycles. This is ideal for experiments that need to take place on a certain day of pregnancy, e.g. if you plan to inject all females with glucose at gestational day 16. It’s much more convenient to have all your pregnant animals reach day 16 within a few days of one another, rather than have to spread out an experiment over 2 weeks because your females all got pregnant sporadically. A note of caution here: females that are group-housed for a long period of time may stop cycling altogether, a phenomenon referred to as the Lee Boot effect after its discoverers (1). However, if this happens, all is not lost. See tip #2.

- Putting soiled male bedding in female mouse cages exposes them to the male pheromones that trigger estrus—the phase of sexual receptivity. This is called the Whitten effect (2). By exposing females to male bedding, you can synchronize their cycles. You can also cause females who have stopped cycling to start again, as long as they’re not too old, which leads to tip #3.

- Use older males (10–12 weeks) over younger ones for increased maturity (they are called “studs” for a reason!). Use females 6–8 weeks old, which are at the peak of maturity. Older females can be used, but no older than 15 weeks, as they are then heading to the geriatric stage (~18 weeks and over) with irregular estrus cycles.

- Use males that have already mated successfully previously (studs) for breeding, and allow males a week between mating sessions. They need time to get their reproductive juices flowing again.

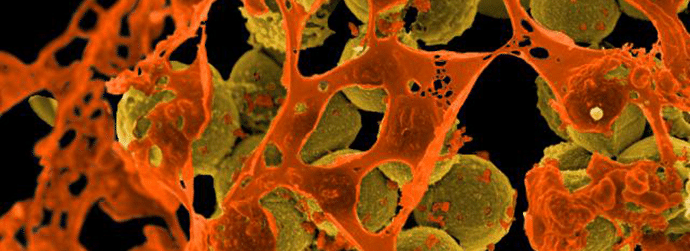

- Don’t expose pregnant females to other males within 5 days of pregnancy. The same exposure to pheromones that stimulates estrus can cause something called the Bruce Effect (3), where the presence of a male mouse prevents embryo implantation, causing pregnancy loss. This allows that second male to mate with the female and produce his own offspring. Selfish, much?

- A copulatory plug is present in the female’s vagina 8–24 hours after mating; visually checking for a plug can confirm that copulation has taken place, and the mouse is likely to be pregnant. Plugs may harden and fall out if you wait too long to check for them. Mating in the afternoon and checking early in the morning is a good strategy.

- Mating success is highest on day 3 of mating: 40–50% of plugs are observed then. Don’t give up on your animals too early.

- The estrus cycle is 4 days long, so keep checking for a copulatory plug for 4 days (5 at the most). This gives each female a chance to go through her cycle once. At this point males that don’t impregnate a female should be replaced.

- Mate one male to 2 females at a time. Any more females and they will take a longer time to mate with them.

- This one is pure magic but I’ll throw it in there. We found that putting a lid on the cage improved our pregnancy rates after obtaining plug positive females. Why? Not sure—maybe something to do with reduced exposure to male pheromones if there are males in cages close by.

With these tips in mind you are on your way to becoming a master breeder! Make sure you also check out our advice for working with mice in the lab. What are some tried-and-tested strategies you use for obtaining reproductive success in your mouse matings?

References

- Van der Lee S, Boot LM. Spontaneous pseudopregnancy in mice. II. Acta Physiol Pharmacol Neerl. 1956; 5: 213–215.

- Whitten WK. Modification of the oestrous cycle of the mouse by external stimuli associated with the male. J Endocrinol. 1956; 13: 399–404.

- Bruce M, An H. Exteroceptive Block to Pregnancy in the Mouse. 1959;184:105. doi: 10.1038/184105a0.