Unless you are one of those rare breeds that do organization naturally, setting a system in place to archive your experiments takes practice and perseverance. It’s hard to imagine when you are doing an experiment for the 100th time that you will ever forget how to do it; but a year down the line, when you’ve moved on, things get rusty. That’s when your PI asks you to do experiment 101. As you rifle through your logbook, it becomes clear that you never wrote down the precise conditions of what worked best or the little things that you changed. How long did you dialyze for? At what temperature? Was that 50 mM or 200 mM NaCl you used that time when the protein band was so perfectly pure that you let out a whoop of joy?

Here are some tricks that I have found handy over the years from learning the hard way!

1. Take Time to Write Your Log

Don’t leave it until the last minute on Friday evening when you would rather be at the pub, beer in hand. The best, and in the end least painful, method is to take some time at the end of the day to write your logbook. This can also be a chance to gather your thoughts on the bigger perspective of the experiment (i.e. what are the questions you are trying to answer in the small and big pictures) and to plan next steps. Plus, if you’ve taken the time to write everything down, it makes you look smart when the first thing your PI wants to know is how things are going before you’ve even had your first coffee.

2. Use a Rough Book

I’m not a tidy note-taker. I use a rough notebook to scribble in and a logbook to write neatly or at least legibly. My lab is now fully electronic in terms of logging experiments (yippee!), which makes the rough notebook invaluable.

Enjoying this article? Get hard-won lab wisdom like this delivered to your inbox 3x a week.

Join over 65,000 fellow researchers saving time, reducing stress, and seeing their experiments succeed. Unsubscribe anytime.

Next issue goes out tomorrow; don’t miss it.

3. Have One Logbook Per Project

When you start a new project, start a new logbook. For example, one sunny day, your PI comes up with a new idea he/she wants you to test. You set up the experiment and start a logbook. Three months later, a new project takes off and you add it to your logbook. Every now and then you do some experiments on project one. A year later, project two reaches completion (hopefully positive!) and now you need to go back to project one. But the experiments are scattered through project two and you spend several hours trying to gather exactly what conclusions you made and what is the best way forward. If you had a logbook for project one and a different one for project two; it’s all there, no searching! Well, almost no searching.

4. Keep a Summary List

For example, if you are making protein preparations, make a list of the date of the expression culture, how you harvested it and relevant growth details, such as inducer concentration, growth time before and after induction, volume of the growth flask, and where and how you stored it. When something seems unusual about the results, you can go back and quickly see if something was different in the preparative stages and then go to your logbook to see more details as necessary. You can also use this to keep tabs on which culture/prep you have used and which is therefore no longer in storage in the freezer. The perfect prep only has so many aliquots!

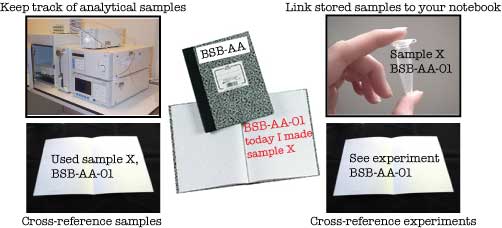

5. Computer Filing

Make folders for projects and use a standardized naming format. It’s amazing how this can suddenly get out of hand. Here’s a scenario: a post-doc arrives at her new lab. Things start slowly as she learns the ropes and she stores the few new files on her desktop, noting their location. People e-mail articles and protocols and onto the desktop they go. A few months go by, and the screensaver of a beach at sunset is covered with files. A colleague e-mails asking for some information, which she knows with certainty she stored in the upper right-hand corner of the desktop just under the cloud with the golden lining. It’s no longer there! Searching for keywords only brings up a different project with closely related keywords. She goes quietly bald tearing her hair out. So, keep your hair on, use the computer to your advantage and give projects a unique name and even a number in a new folder. Date all your documents when you save them and include the unique name or number. Put in as much information as you can.

Here is an example:

Folder name for project: 001 Protein A expression and purification

Subfolder: Bacterial culture of protein A

Document: 21Sept2015 Protein A expression levels at 0.1 and 1mM IPTG, 37ºC

In this way you can find what you are looking for much more rapidly and your PI will be impressed when s/he sends you an e-mail requesting a PowerPoint slide from a lab meeting 3 months ago and you e-mail right back with the slide in question

6. Be Consistent

It may sound excessive but keeping your logbook naming and filing system consistent is also really helpful. For example, always start with the date in the same format, or use a consistent order of conditions used in your protocols (e.g. strain of bacteria, growth temperature, volume, induction level). You can even create a template and use that every time. For instance, create a blank PCR template and fill it in whenever you do a new PCR. Add the little things like percentage agarose for the gel and how much sample was loaded. Yes, you might ALWAYS use 1% or load 10µl, until one day you decide to try something different and use 1.5% and 5µl. If you don’t note it, you won’t remember that you did it.

7. Write a Conclusion

At the end of the experiment, when you have recorded your results, write a summary statement as to what they mean. This will help direct your thoughts to answering the question at hand and be useful when you are looking back at experimental conditions and their outcome.

You made it to the end—nice work! If you’re the kind of scientist who likes figuring things out without wasting half a day on trial and error, you’ll love our newsletter. Get 3 quick reads a week, packed with hard-won lab wisdom. Join FREE here.