Maybe you’re studying blood cells using hematology microscopy, or maybe you’re after genetic material or circulating biomarkers. Whether you’re performing blood cultures or isolating normal B cells, you may find yourself needing human blood samples.

For many scientists, getting blood specimens can be intimidating.

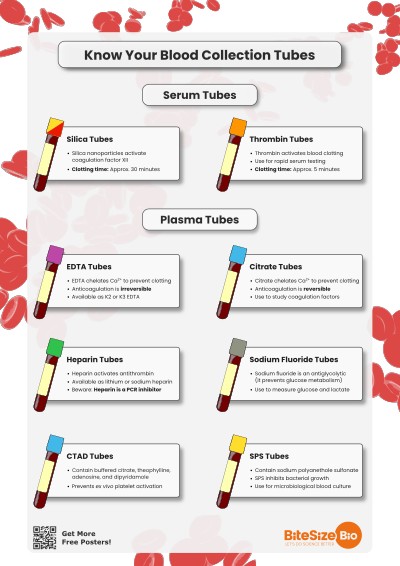

In this short article, we explain different blood collection tube types, including plasma tubes, serum tubes, and anticoagulant tubes, and their key differences.

Blood Collection Tube Types

Whether you’re collecting your samples in-house or through a clinic, hospital, or pathology center, you’ll need to have a good idea of what kind of blood collection tubes suit your purposes. The first thing to check is your protocol—for example, some ELISAs will specify the types of samples you can and can’t use with certain tubes. Thinking about specimen requirements before you get started can save a lot of headaches later!

But what if your protocol doesn’t specify, or you’re adapting a method from another system, or you want to make sure you’re storing the best type of sample for future not-yet-defined analyses? Hopefully, I can help you find your way around all those differently colored tubes.

A quick note about those cap colors before we begin: I’ve listed them below, and the color-coding system is generally pretty consistent, but I can’t promise the colors are the same in every company producing blood collection tubes, so always check first!

Serum vs. Plasma Tubes

The first thing to figure out is whether you want to collect serum or plasma. That depends on whether or not you need to stop the blood from clotting.

Don’t confuse serum with plasma—while they’re both the liquid, cell-free part of the blood you can obtain by centrifugation—they are critically different:

- Serum is the product of blood that has been allowed to clot.

- Plasma is the product of blood that has been prevented from clotting with an anticoagulant.

Therefore, You need to use either a serum collection tube or a plasma collection tube, respectively.

1. Serum Tubes

Blood serum is a great (and stable) way of measuring the blood’s proteins, lipids, hormones, electrolytes, etc. Many of these markers can be stored for days in the fridge or frozen down and measured in batches later.

There are two main types of serum collection tubes that differ in how they activate blood clotting, using different clot activators.

Silica-Based Tubes

These tubes have silica nanoparticles, which activate clotting by activating coagulation factor XII. Some also have a gel to separate the serum—if you’re looking for a protein that isn’t involved in coagulation, these are probably the tubes for you.

Those without the separating gel are usually more useful in sensitive diagnostic testing.

Note that their color usually depends on their brand. Becton Dickinson tubes are commonly gold but also red, while Greiner Bio-One tubes are red. Compared to thrombin-based tubes, it takes longer for blood to clot in silica-based tubes.

Clotting time: Approximately 30 minutes.

Thrombin-Based Tubes

These tubes use thrombin to activate blood clotting. They’re mainly used clinically for tests that are needed especially quickly. However, some serum components are a little less stable in these tubes.

Note that these tubes are usually orange.

Clotting time: Approximately 5 minutes.

2. Anticoagulant Tubes

This is the category to consider if you need cells or plasma (a cell-free liquid that still contains coagulation factors).

EDTA Tubes (Purple)

EDTA prevents clotting by chelating calcium, an essential component of coagulation. Depending on what you are doing, EDTA in blood collection tubes could be a disaster!

EDTA blood collection tubes are your basic hematology tubes (by which I mean identifying and counting blood cells, blood typing, etc.).

Plasma stored from EDTA-treated blood can also be used to measure most proteins, and genetic material can easily be stored from EDTA buffy coats (the interface between the red cells and the plasma after centrifugation, containing white cells and platelets).

Note that these tubes contain either K2EDTA (dipotassium) or K3EDTA (tripotassium). Beware that K3EDTA is more hyperosmolar due to the extra potassium ion—meaning it will concentrate blood samples more than K2EDTA via the hyperosmolar effect.

Sodium Citrate Tubes (Light Blue)

For coagulation and platelet function tests. Like EDTA, citrate removes calcium from the blood by chelating it. Unlike EDTA, it’s reversible—so calcium can be added back to study coagulation under controlled conditions. Citrated plasma is also used to measure coagulation-relevant factors.

It’s worth noting that a citrate tube should not be the first type of tube filled after venepuncture—the first few mL of blood drawn will be a bit activated. If you only need samples collected in citrate blood collection tubes for your project, you should collect a “discard” tube first.

Also, note that different citrate concentrations are available from different companies, so check this before you buy them.

CTAD Tubes (Also Light Blue)

CTAD stands for citrate, theophylline, adenosine, and dipyridamole. These aren’t common but are worth knowing about—they prevent ex vivo activation of your platelets, making them useful for some more sensitive platelet function and coagulation studies.

Note that CTAD is light-sensitive, so keep these guys in the dark.

Heparin Tubes (Green)

These tubes can contain either lithium heparin or sodium heparin. They are similar to serum clot activator tubes, but suitable for tests in plasma rather than serum. Like serum tubes, heparin tubes for blood collection may also have a separating gel. Heparin acts by inhibiting thrombin formation.

If your endgame is PCR, you should be aware that heparinized plasma samples may not be suitable as heparin inhibits reverse transcription and PCR amplification, meaning it can severely interfere with PCR reactions. [1]

However, whichever anticoagulant you choose, you may need to allow for it in your reaction mix. You can overcome heparin inhibition by treating your PCR mix with heparinase. Adding a crowding agent such as bovine serum albumin or diluting your PCR mix may also work.

Sodium Fluoride Tubes

Sodium fluoride is an antiglycolytic agent (it prevents glucose metabolism), so these tubes are used for glucose and lactate testing. They also contain an anticoagulant.

Acid Citrate Dextrose—ACD Tubes (Yellow)

These are not common, but they are used for blood and tissue typing and DNA analysis.

Sodium Polyanethol Sulfonate—SPS Tubes (Yellow)

SPS stabilizes bacterial growth, so they are useful for microbiology applications.

Types of Blood Collection Tubes Summarized

For more specific purposes, there are additional types of blood collection tubes out there, but hopefully, this has given you a handle on where to start. Remember to consider whether you want plasma or serum, and pick your tube accordingly.

Good luck with your experiments, and welcome to the world of—let’s be honest—feeling just a little bit like a vampire.

Note: Please remember to always wear protective equipment when working with blood, including safety goggles, gloves, and laboratory coats, and work carefully to avoid contact with blood and blood exposure.

It’s important to consider the safety of yourself and others in the lab. Watch the on-demand webinar on centrifugation to discover the dangers of aerosols from centrifugation and how to prevent them.

Since you’re here, why not download Bitesize Bio’s handy blood collection tubes chart and pin it up in your lab—It’s free!

Originally published May 2015. Reviewed and updated August 2023.

Reference

- Kondratov K, Kurapeev D, Popov M, et al. (2016) Heparinase treatment of heparin-contaminated plasma from coronary artery bypass grafting patients enables reliable quantification of microRNAs. Biomol Detect Quantif 8:9–14