This article mentions of suicidal thoughts. If you are having thoughts of self-harm, I encourage finding someone to talk to. It can be a family member, friend, or professional counselor. Many countries also have suicide hotlines.

Mental Health is often not a priority for institutions or individuals in academia. Making institutions friendlier will take time, but there are many things individuals can do to take care of themselves. Academia is hard on people. There is no shortage of reports and personal accounts about the toll of academia on mental health. However, there is some good news: campaigns envisioning scientists as full humans with lives outside the lab.

Here is a partial list of things that make academia challenging:

- Constant rejection (It’s possible to train to get more used to it)

- Career uncertainty

- Thesis ups and downs

- Intense, hypercompetition in a tight funding environment

- The publish or perish mentality taken to extremes

- Expectations of perfection (leading to fixed mindsets & rampant impostor syndrome)

- The idea that any time not spent on science is wasted

- Deep seated assumptions (distortions?) about what successful scientists/careers look like–the lone “genius” in an ivory tower

- Success only defined by the tenure track faculty position with “failure” being anything else. Despite the fact that academia is not the default path for of Ph.D.s

- Career transitions can be hard

That list can lead to perfectionism, burnout, isolation, and even worse: depression and anxiety– the most prevalent mental illnesses. When a brain is interfering with day-to-day life for weeks, seek help. Mental illnesses are real and treatable even if we are still working to effectively diagnose and understand them. I asked a depression researcher what makes depression so hard to treat:

“Most of the available treatments were discovered through serendipity, which means that they weren’t rationally designed to treat the underlying biological problem in the brain—a problem that many depression researchers are still working to understand. Because we’re still working to explain the malfunctioning biology that causes depression, medical professionals are left with an incomplete toolkit in working with people who have depression, and they face a number of challenges: 1) depression is hard to diagnose (and can manifest very differently for different people), and we don’t have good biological markers to “measure” depression; 2) many people with depression have very different responses to different treatments, and this can be hard to predict without trial-and-error (which frequently takes months); and 3) since depression is primarily a disorder of the brain, we have to be very careful to design treatments that won’t damage or disrupt the other functions in the brain.”

Taking care of mental health in what can be the harsh, stressful, environment of academia can seem impossible when suffering. There are no certain answers and it does take effort. However, there are some things, besides counseling/medication, that seem to help a lot of people:

- Realize you are not alone. Andrew Solomon has a great talk on depression.

- Find or build a community and a support network.

- Exercise and get outside. Have a self-care plan

- Remember: Disability is not disqualification.

- Cultivate a growth mindset and resilience.

- Incorporate some self-compassion into your routine.

- Develop a sense of being enough, as you are now.

- Challenge depressive thoughts when they occur. Break the rumination cycle.

- Learn about cognitive distortions & realize when you’re engaging in distorted thinking.

- Get curious about what is known about what happens in the mentally ill brain (e.g., Jonathan Rottenberg’s book, The Depths).

I asked the depression researcher about some avenues scientists are pursuing to better understand and treat depression as well:

“Because depression is thought to be a disease of malfunctioning brain circuits, one exciting avenue for research is trying to understand how these circuits “break” in depression. Many researchers like me are trying to understand the function of families of molecules whose primary role in the brain is to regulate the formation and maintenance of brain circuits, and we’re finding that these molecules are among the most altered in depression. However, because these molecules have other functions that are important for healthy development (and whose malfunction has been implicated in other diseases, like cancer), we have to study these molecules very carefully so that we don’t inadvertently design a treatment that does more harm than good.”

My Depression Management Story

A few years ago, I could no longer tell signal from noise. There seemed to be no significant difference between living or not. I knew there were still people out there who cared about me and that kept me going. I was also aware that depression, anxiety, and many other mental illnesses are treatable, if imperfectly.

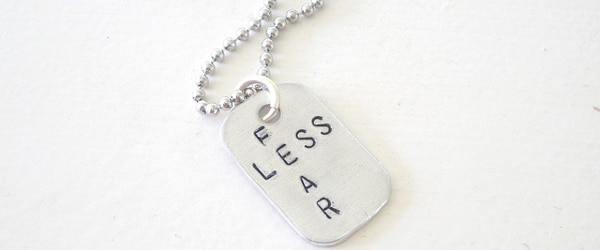

I saw a therapist and begrudgingly started an antidepressant. And I exercised. The combination lessened the depressive voice enough to give me an opportunity to cultivate a more hopeful and resilient one—a credible alternative to depression. Learning to challenge depressive thinking/cognitive distortions took time. I do it almost automatically now. I filled my head with voices— mostly from the internet— that were positive, but not positive for positivity’s sake. I sought grounded voices that resonated with me. Lifehacker was a particularly good resource. As were books like Susan Cain’s Quiet. Comedian-musicians Garfunkle & Oates have a song, ‘Such a Loser’ (NSFW: profanity) demonstrating the ‘realistically optimistic’ view. It acknowledges that life is hard while praising showing up and standing in the arena again and again— to keep going.

I started a blog to chronicle my journey through depression and my postdoc. I joined Twitter to connect with people. I have steadily risen from a stalled life to one where I feel a future exists. I am still exploring and having some successes with writing about science, and exploring ‘science adjacent’ careers in the writing/editing/education realm. It’s been a long journey and not everything is perfect. But as Andrew Solomon said, the opposite of depression is not happiness, it’s vitality. And I feel I’ve come back to vitality.