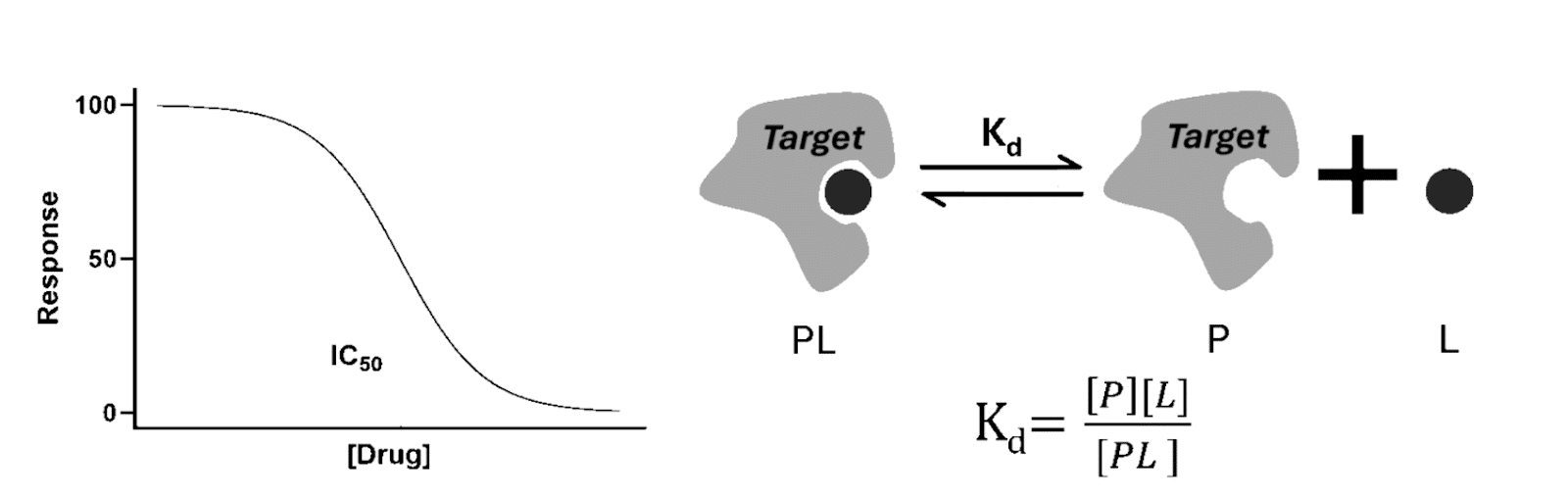

When you’re screening compounds in the early stages of drug discovery, you’ll encounter two metrics again and again: IC₅₀ and Kd (Figure 1). Both appear as simple numeric values in summary tables and database entries, which makes them look interchangeable at first glance. Understanding how to interpret IC50 and Kd correctly will reveal why they’re not.

This resemblance creates a persistent problem in lead optimization. You might assume that a low IC₅₀ automatically means tight binding, or that you can directly compare IC₅₀ values from different labs without considering their assay conditions—a mistake that comes from not thinking carefully about how to interpret IC50 and Kd in context. [1]

These assumptions lead to flawed decisions, like ranking compounds incorrectly or missing selectivity issues that only become apparent when you understand what each metric actually measures.

Here’s what distinguishes them:

- IC₅₀ describes functional potency—how effectively a compound inhibits a biological process in a specific assay.

- Kd describes thermodynamic binding affinity—how tightly a compound binds to its target under equilibrium conditions. [2]

Understanding this distinction transforms how you interpret screening data and prioritize compounds.

Figure 1: Conceptual diagram comparing IC₅₀ (functional response) vs Kd (binding equilibrium). [3]

What IC50 Really Measures

IC₅₀, or half-maximal inhibitory concentration, tells you the concentration of compound needed to reduce a biological process by 50%. That process might be enzyme activity, a cellular response, or a signaling cascade—whatever your assay measures.

What makes IC₅₀ practical is also what makes it complicated: it’s an operational measurement.

You fit dose–response curves to your experimental data, and the IC₅₀ falls out of that analysis. Because it’s a functional readout, it captures the composite effects of your entire system, not just the binding event between drug and target.

This means IC₅₀ values are highly sensitive to experimental conditions. Change your target protein concentration, adjust your substrate levels, or switch to a different readout, and you’ll get a different IC₅₀ for the same compound.

In lead optimization, IC₅₀ remains the most common way to track on-target activity, but you need to know the assay details to interpret it correctly.

A common misconception is treating IC₅₀ as a universal property of a compound, when it’s actually a property of the compound-assay combination.

What Kd Actually Represents

Kd, the equilibrium dissociation constant, measures something fundamentally different: the intrinsic binding affinity between your compound and its target. At equilibrium, Kd is the concentration at which 50% of the target’s binding sites are occupied.

Unlike IC₅₀, Kd doesn’t depend on what happens after binding. Substrate concentrations, downstream signaling, cellular responses—none of these affect the Kd value. This independence makes Kd ideal for comparing compounds across studies and evaluating selectivity across targets.

You measure Kd directly using biophysical techniques. Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR) tracks binding kinetics in real time. Isothermal Titration Calorimetry (ITC) measures the heat released during binding. Radioligand binding assays (RBA) use displacement of labeled probes. Each method provides a thermodynamic view of the interaction itself, stripped of functional complexity.

This precision matters increasingly as computational and AI-driven models become central to drug discovery. Kd provides a more consistent representation of binding affinity that is increasingly valuable for computational modeling.

Why IC50 and Kd Are Not Directly Comparable

You’ll often see IC₅₀ and Kd values for the same compound that don’t match. This isn’t a measurement error—it’s the expected outcome when you compare a functional metric to a thermodynamic one.

IC₅₀ reflects everything happening in your assay: binding, conformational changes, competition with substrates, and the functional readout itself. Double your target concentration, and you might shift your IC₅₀ by twofold. Use a different substrate concentration, and the shift could be larger.

Kd, by contrast, describes only the binding equilibrium. It does not depend on downstream functional readouts and is less sensitive to assay design than IC₅₀. This difference creates real problems when you work with public datasets like ChEMBL, where IC₅₀ measurements from dozens of labs get pooled together. Without knowing each assay’s specific conditions—information that’s often missing—you’re comparing numbers that may not be comparable at all.

What this means in practice: IC₅₀ values are most useful when you’re tracking compounds within a single assay series. When you need to compare across studies or assess selectivity across targets, Kd gives you a more reliable foundation.

Relating IC50 to Kd: When Does It Work?

Despite their differences, you can sometimes relate IC₅₀ to Kd mathematically—if your assay meets specific requirements. The Cheng–Prusoff equation is the most widely used approach.

For a simple competitive enzyme inhibition assay, it converts IC₅₀ to the inhibition constant (Ki, which approximates Kd) when you know the substrate concentration ([S]) and the Michaelis-Menten constant (Km).

Several assumptions must hold for this conversion to be valid. The inhibitor must bind competitively. You need to know the probe affinity. The system needs to be at equilibrium. In well-controlled biochemical assays, these conditions are often achievable.

When researchers have analyzed large datasets where these parameters are tracked, they find that pKi values typically exceed pIC₅₀ values by about 0.35 log units—roughly a factor of 2.3. For broader datasets where assay details are unknown, a conversion factor of 2.0 is commonly used, corresponding to a balanced condition where [S] equals Km.

More sophisticated approaches like Schild analysis can reduce the number of assumptions required, but demand even tighter experimental control.

A common misconception is that these equations work universally. They don’t. If your assay involves allosteric inhibition, multiple binding sites, or complex cellular signaling, the mathematical relationships break down.

The Challenge of Cellular Context

Moving from purified biochemical assays to living cells adds layers of complexity. In cells, your compound faces challenges that don’t exist in a test tube: membrane permeability barriers, efflux pumps, protein binding, and competition with high concentrations of endogenous ligands like ATP.

These factors make it difficult to measure an intrinsic Kd in live cells. Even when you can measure cellular IC₅₀ values easily, they often don’t tell you much about target engagement. The functional response you’re tracking might be several steps downstream from the initial binding event, and those downstream steps can dominate the measurement.

This creates a practical gap. You have functional potency data from cellular assays, but you lack a clear picture of how much drug is actually binding to your target inside the cell. For understanding mechanism of action and predicting in vivo behavior, this gap is important.

Estimating Apparent Affinity in Living Cells

To address these limitations, probe-displacement approaches have emerged that estimate “apparent affinity” (Kd-apparent) in cellular environments. These methods bridge the gap between functional potency and target engagement.

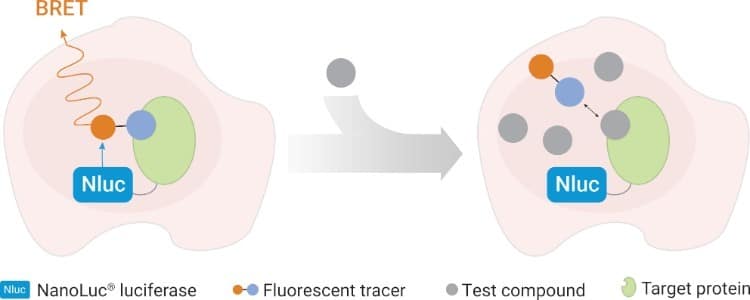

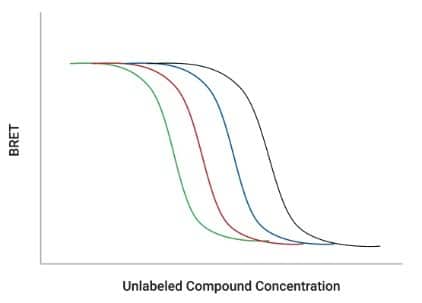

One such approach uses NanoBRET® Target Engagement assays (Figure 2). These assays employ bioluminescence resonance energy transfer (BRET) to measure displacement of a fluorescent probe from your target protein in live cells. When designed carefully, the assay conditions can satisfy the assumptions needed for Cheng–Prusoff analysis.

By applying linearized Cheng–Prusoff equations to the displacement data, you can extract Kd-apparent values directly from IC₅₀ measurements performed in the cellular context.

This distinction matters because Kd-apparent accounts for the cellular environment (permeability, metabolism, and endogenous competition) while still providing a quantitative estimate of target engagement. It’s not the same as the intrinsic Kd you’d measure with purified protein, but it tells you how the drug behaves where it actually needs to work.

Figure 2: Principle of the NanoBRET® Target Engagement Assay showing probe displacement in a live cell (top) and the compound titration curve (bottom). [3]

Explore how NanoBRET® assays support quantitative target engagement in cells.

Summary: Using IC50 and Kd Together, Not Interchangeably

IC₅₀ and Kd answer different questions about your compound. IC₅₀ tells you how much functional effect a compound produces in a specific experimental system. Kd tells you how tightly it binds to its target at equilibrium.

Think of Kd as the strength of a magnet’s pull—an intrinsic property determined by the magnet and the metal it attracts. IC₅₀ is like measuring how effectively that magnet holds a door shut against a specific spring.

The result depends on the magnet’s strength (Kd), but also on the spring’s stiffness and the door’s weight (your assay conditions). Both measurements tell you about the magnet, but only one is independent of the room you’re working in.

The assay-dependent nature of IC₅₀ makes it valuable for tracking potency within a defined series, but complicates cross-study comparisons. The intrinsic nature of Kd facilitates straightforward comparisons of binding affinity and selectivity across targets and studies.

When you integrate both metrics into your drug discovery workflow—using Kd to optimize binding and IC₅₀ to evaluate functional efficacy—you gain a more complete understanding of your compound’s mechanism of action. Knowing how to interpret IC50 and Kd correctly supports better decision-making throughout the development process.

Further reading:

- Kalliokoski, T., et al. (2013) Comparability of Mixed IC50 Data – A Statistical Analysis. PLoS One 8(4), e61007.

- Ma, W., et al. (2018) Overview of the detection methods for equilibrium dissociation constant KD of drug-receptor interaction. J. Pharm. Anal. 8(3), 147-152.

- Promega Connections: Exploring the Relationship Between IC50 and Kd in Pharmacology