Is In Vitro Translation (IVT) a Good Choice for You?

With in vitro translation (IVT) you can produce protein in a tube. Cool sure, but would IVT be a good choice for your experiments? Not sure? Then read on. Here I will cover the strength and weaknesses of IVT.

How In Vitro Translation works

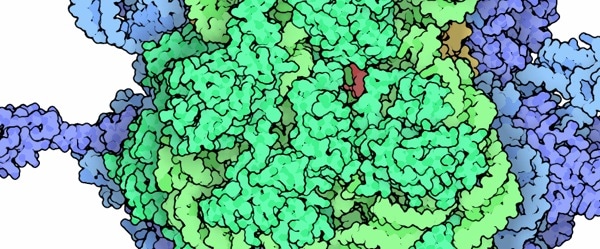

First things first, for IVT you need ribosomes. While theoretically possible, making artificial ribosomes is still not feasible. So you will need to get your ribosomes with subcellular fractionation to create a ribosomal-rich IVT lysate. To do this you can follow one of the many (relatively) straightforward techniques to make your own IVT lysate from almost any cell type or you can use one of the many commercially available kits.

After you obtain your ribosome-rich lystate you then need to combine it with mRNA (or cDNA, if you use a Combination kit) template, some ATP for energy, and a supplement of mixed amino acids, then your protein factory is up and running! Depending on the type of lysate and volume of the reaction mix, a typical in vitro translation can produce more than 100 ?g of protein. Not too shabby. After performing IVT, you will usually need to purify your protein from the lysate. There are many ways to do this, but most often people will use an affinity tag on their recombinant protein, or an immunoprecipitation assay.

When In Vitro Translation is a Good Choice

IVT offers a simpler and faster method for producing ?g quantities of peptides, in a tube, without having to do a cell culture and transfection. It is also useful for producing proteins that would be toxic to cells, or originate strong signaling responses. Particular examples include:

- Transcription factors. When transcription factors are produced in cell culture, they can cause irregular signaling responses in host cells. Ultimately, this can lead to poor yields of your protein. However, in IVT there is no nuclear DNA for these proteins to interact with, and therefore no spurious signaling feedback to the translational machinery.

- Toxins. Many proteins can be toxic to the host cells, especially when produced in large quantities in culture. This includes many proteases and kinases – the most commonly studied class of signaling molecules.

- Other problem proteins. Proteins that form inclusion bodies or undergo rapid breakdown inside cells – whether it is part of their natural lifecycle, or an artefact of overexpressing them in cell culture, some proteins are just difficult for cultured cells to tolerate. Expression through IVT can therefore protect your proteins from cellular processes that would otherwise render them useless.

When In Vitro Translation is Not so Good

IVT relies on essentially “borrowed” cellular machinery and this machinery (the proteins and RNA) rapidly breaks down when outside of the friendly confines of a cell. This means there is an effective time-limit on the molecules in your IVT experiments, after which the yield and size (up to about 300 kDa in really good commercial kits) of your protein will suffer.

IVT is also not very good for producing functional complex proteins, or those that have extensive tertiary structure. The peptides produced by purified ribosomal machinery will most often thermodynamically settle into their appropriate secondary structures of alpha helices and beta sheets. However, without the machinery associated with cell organelles, such as endoplasmic reticulum and golgi body, complex post-translational modifications are not possible in an IVT experiment. For the same reason, proteins with extracellular modifications such as sulfide bridges and glycosylation cannot be fully produced using IVT.

Other Important Considerations

With so many IVT kits and protocol options out there, how can you choose which one is for you? First of all, it is important to use a lysate that is appropriate for the type of genetic template you are using. Although the basic genetic code is universal, prokaryotes and eukaryotes use slightly different ratios of the various tRNAs for each codon. And while there are up to 4 possible tRNA codons for each amino acid, most living cells primarily only use one or two, and may contain hardly any tRNA for their less-commonly used codons. This means that if your system is not optimized for your mRNA (or vice versa) tNRAs can became rate-limiting and severely restrict your yields.

To prevent this from becoming your problem, always choose a lysate that is derived from at least the right Kingdom as your mRNA template. If you can use a lysate that is from the same genus or even species as your protein, your IVT will be even more efficient.

The 411 on Getting In Vitro Translation Right

- Remember, IVT uses the synthetic machinery from a cell, but does not provide the protection a cell gives to newly-synthesized proteins. Always keep all items on ice at all times (except when performing the translation reaction itself!).

- If you make your own ribosomal lysaste, remember to add a simple protease inhibitor cocktail. The ribosomal lysate should be used as fresh as possible, or stored at –80°c in single-use aliquots, to protect it from freeze-thaw damage.

- The most critical aspect of your IVT assay is the quality of your mRNA or cDNA template. Fragmented or broken ribonuclease templates, or impurities in your sample, will certainly lead to poor results in your IVT reaction.

- For more advise on IVT see “Think You Need Cells to Make Protein? Think Again! Use In Vitro Translation.”